|

|

|

|

The entire approach to the Mount St. Helens Volcanic Monument was conceived of as a 60-plus mile ecclesiastical journey. From the highway approach “nave,” to the visitors complex “transept,” and the metaphorical terminus at the crater “apse,” visitors undertake a journey that is ultimately and explicitly more powerful than themselves (photo: CALA/Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture). |

|

|

|

|

|

Like modern day pilgrims, visitors flock to the prow of the Johnston Ridge Volcano Observatory, which feels like a teetering altar. This proscenium stage provides an unparalleled setting for contemplation of the beauty of the devastation beyond (photo: USFS/United States Forest Service). |

|

|

|

|

|

In plan, the Coldwater Ridge Visitors Center is organized around a ridge rim arc with an arrow orienting visitors toward the crater and piercing its heart (photo: CALA/Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture). |

|

|

|

|

|

Within the construction envelope, ejected debris was catalogued and later replaced in its original location. Boulders cast from the mountain and blown down trees are compass needles pointing away from the crater’s devastating force, while the site interventions orient viewers directly toward the crater (photo: Andrew Buchanan). |

|

|

|

|

|

The building entry features fractured pavement and specially designed light elements that are reminiscent of the once towering trees that now lay scarred and prostrate on the ground (photo: Andrew Buchanan). |

|

|

|

|

|

From 1993, when it opened to the public, to 2005, plant life at the Coldwater Ridge Visitors Center has slowly returned. It is a gradual, delicate process that speaks volumes about the fragility of the landscape (photo: EDAW/Strode-Eckert Photography). |

|

|

|

|

|

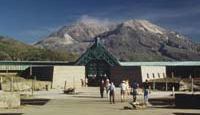

A spring 2005 view of the main entrance to the Coldwater Ridge Visitors Center provides an indication as to how an entire alpine ecology dominated by lupine, penstemon and fireweed has established a strong foothold (photo: Andrew Buchanan). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GENERAL DESIGN AWARD OF HONOR

Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, Coldwater/Johnston

Recreation Complex, Castle Rock, WA

Charles Anderson Landscape Architecture, Seattle, WA

EDAW, Inc., Seattle, WA

USDA Forest Service, Vancouver, WA

|

|

|

When the snowy cathedral of Mount St. Helens erupted on

May 18, 1980, the world witnessed the terribly beautiful and surreal

speed with which a pristine wilderness could be transformed

into a paradoxical and enigmatic landscape. This May, 25 years

later, Mount St. Helens demands our attention as the mountain

rebuilds and pilgrims flock to the Forest Service facilities

at Coldwater Ridge and Johnston Ridge to once again bear witness

to the mountain’s majestic fury.

Conceived on a master plan level as a 60-mile ecclesiastic

experience, visitors enter the “church” upon exiting

Interstate 5 onto the new road leading to the monument. This

central "nave"—long, narrow, atoning—prepares

visitors for the crater-cum-altar within the conceptual "transept"

of the blast zone where the two facilities are located. The

immolated past is laid bare in this surreal landscape of prostrate

trees, denuded soils, and funereal memorials. The continuation

of the spiritual journey—from earth to ether—is

purely a metaphorical construct, yet standing on the fractured

prow of the Johnston Ridge Observatory while confronting the

apse (crater), visitors are connected to the powerful, terrifying

and, ultimately, deeply beautiful face of the unknown.

For many of the survivors who experienced the mountain’s

power, the memory is more emotion than experience. It was

this primal wellspring that provides the foundation for the

site design at both locations: awe, fear, joy, terror, reverence.

Fractured pavement gives the feel of a burnt, unstable firmament.

Custom light poles read as stripped but standing tree trunks

during the day and become illuminating beacons at night. There

is also the psychological perception of permanence. Rather

than terraced landforms to accommodate the seasonal crush

of vacationers, the designers approached parking as a buried

ruin that was dug out from beneath the blast debris and ash.

It was a counter-intuitive move that lead to the massive earthwork

creation of a plateau for parking using the cut material from

the new highway’s construction. These moves also met

the goals of the collaboration between the public and private

sector clients: an interdisciplinary design that was deferential

to the mountain and its resources, yet evocative and expressive

in its own right.

T he Coldwater Ridge Visitors Center takes the crescent shape

of the volcano and imposes an arrow oriented to the crater.

A network of paths thread visitors through the devastated

cloisters where great trees once stood and overlooks provide

moments of pause and praise. Here, and at the Johnston Ridge

Observatory further on, planting design was conducted with

an restrained hand. Life, here, is delicate and primeval;

a precarious balance that was part brownfield and part intensive

ecological restoration. For these reasons the majority of

the site was left to sustain and succeed on its own—as

a laboratory where life, once tenuous, was now spreading its

tendrils slowly. Where plantings were justified, the designers

specified only plants that were growing within the monument.

Even the blown down logs and "volcanic bombs" (superheated

boulders that flew up to eight miles from the eruption landed

and split apart) were cataloged and returned to the construction

envelope.

Both memorial and monument, the Johnston Ridge Observatory

poignantly displays the drama of the destruction and becomes

the visitor’s penultimate experience along the emotional/spiritual

journey through the metaphor of a resting butterfly. The butterfly

is a symbol of beauty, delicacy, and durability. It is a creature

that quickly returned to the devastated landscape and symbolizes

the vital forces of this landscape. The butterflies returned

without memory of the eruption, seeking the nectar of the

lupines, penstemons, and fireweed that were quick to cover

the blast zone.

Human visitors return to the site seeking another type of

sustenance. So that visitors may concentrate on the power

of the mountain, the design deliberately minimized the view

of the road and parking area from the observatory. Moving

from drop off to the earth-sheltered observatory, visitors

walk an ash-laden arc that has been sliced through the ridge.

Both allegorical and functional, the meander of this trail

pushes visitors further outside traditional zones of comfort

in anticipation of the proscenium thrust of the mountain.

The volcano emerges from beyond the balcony overlook, which

drops down slightly to increase the sense of liminal imbalance

and uncertainty. With a 2,000 foot drop and the looming mountain

just five miles distant, the choreography of the landscape

ends on a teetering altar.

Rather than inciting fear for disingenuous reasons, the designers

have delicately balanced the extant power of the mountain

to awe and inspire with the human desire to connect with a

power beyond themselves. The spaces bow to and highlight an

omnipotence only imagined 25 years ago. At the same time,

they continue to inspire visitors through emotional awe and

a deeply-resonant respect that reveals both the brutal and

delicate processes of survival, regeneration and reformation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|