News

Interview with Richard Weller

Richard J. Weller, ASLA

Richard J. Weller, ASLA

Later this year, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) will meet in China to finalize what is being called a “Paris Agreement for Nature.” The agreement will outline global goals for ecosystem conservation and restoration for the next decade, which may include preserving 30 percent of lands, coastal areas, and oceans by 2030. Goals could also include restoring one-fifth of the world’s degraded ecosystems and cutting billions in subsidies that hurt the environment. What are the top three things planning and design professions can do to help local, state, and national governments worldwide achieve these goals?

Design, Design, and Design!

There are now legions of policy people and bureaucrats, even accountants at the World Bank, all preaching green infrastructure and nature-based solutions. But the one thing all these recent converts to landscape architecture cannot do is design places. They cannot give form to the values they all now routinely espouse.

But design is not easy, especially if it’s seeking to work seriously with biodiversity, let alone decarbonization and social justice. Design has to show how biodiversity— from microbes to mammals— can be integrated into the site scale, then connected with and nested into the district scale, the regional, the national, and, ultimately, the planetary scale. And then it has to situate the human in that network – not just as voyeurs in photoshop, but as active agents in ecosystem construction and reconstruction.

Of course, wherever we can gain influence, this is a matter of planning — green space here, development there. But it’s also an aesthetic issue of creating places and experiences from which the human is, respectfully, now decentered, and the plenitude of other life forms foregrounded.

It’s as if on the occasion of the sixth extinction, we need a new language of design that is not just about optimizing landscape as a machine, or a pretty picture, but that engenders deeper empathy for all living things and the precarious nature of our interdependence.

In 2010, the CBD set 20 ambitious targets, including preserving 17 percent of terrestrial and inland waters and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas by 2020. Of these targets, only 6 have been partially met. On the other hand, almost every week, we hear about billions being spent by coalitions of foundations or wealthy individuals to buy and protect vast swathes of land in perpetuity. And the protection of nature and leveraging “nature-based solutions” is increasingly a global priority. Are you positive or negative about the future of conservation?

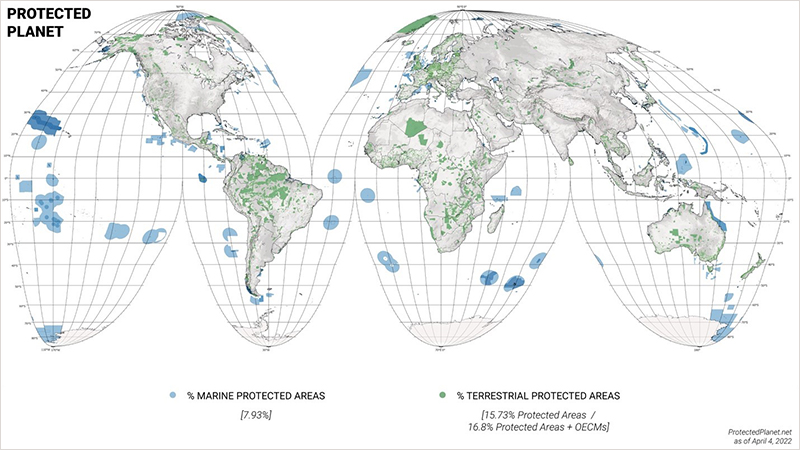

In 1962, there were about 9,000 protected areas. Today, there are over 265,000 and counting. I our yardstick is humans setting aside land for things other than their own consumption, then there is reason to be optimistic.

In 2021, the total protected area sits at 16.6 percent the Earth’s terrestrial ice-free surface, not quite 17 percent, but close. The missing 0.4 percent is not nothing – it’s about 150,000 Central Parks and over the last few years my research has been motivated by wondering where exactly those parks should be.

The World’s current protected areas. Image by Rob Levinthal, courtesy Richard Weller

The World’s current protected areas. Image by Rob Levinthal, courtesy Richard Weller

The fact that humans would give up almost a fifth of the Earth during such a historical growth period is remarkable in and of itself. While targets are useful political tools, the question is one of quality not just quantity. And that’s where pessimism can and should set in. Protected areas, especially in parts of the world where they are most needed, arise from messy, not to say corrupt, political processes. They are not always a rational overlay on where the world’s most threatened biodiversity is or what those species really need.

The percentages of protected areas around the world are also very uneven across the 193 nations who are party to the Convention. Some nations, like say New Zealand, exceed the 17 percent target, while others, like Brazil fall way short – and they don’t want people making maps showing the fact. Protected areas also have a history of poor management, and they have, in some cases, evicted, excluded, or patronized indigenous peoples.

Protected areas are also highly fragmented, which is really not good for species now trying to find pathways to adapt to climate change and urbanization and industrialization. The global conservation community is keenly aware of all this but again, while they are good on the science and the politics, they need help creating spatial strategies that can serve multiple, competing constituencies. Under the Convention, all nations must produce national biodiversity plans, and these should go down to the city scale, but these so-called plans are often just wordy documents full of UN speak. There is a major opportunity here for landscape architects to step up.

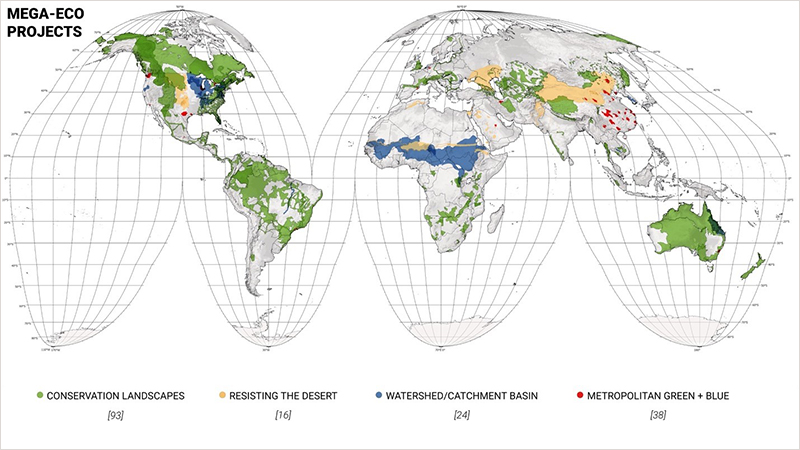

So, the pessimist’s map of the world shows the relentless, parasitical spread of human expansion and a fragmented and depleted archipelago of protected areas. The optimist’s map on the other hand shows over 160 projects around the world today where communities, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are reconstructing ecosystems at an epic landscape scale.

Rob Levinthal, a PhD candidate at Penn and I call these Mega-Eco Projects. As indicators of the shift from the old-school engineering of megastructures towards green infrastructure on a planetary scale, they are profoundly optimistic.

Mega-Eco Projects taking place in the world today. Image by Rob Levinthal, courtesy Richard Weller

Mega-Eco Projects taking place in the world today. Image by Rob Levinthal, courtesy Richard Weller

We don’t call these projects Nature Based Solutions. The reason being that “nature” comes with way too much baggage and “solution” makes designing ecosystems sound like a simple fix. These two words reinforce a dualistic and instrumentalist approach, things which arguably got us into the mess we find ourselves in today.

By placing the Mega-Eco Projects within the tradition of 20th century megaprojects — many of which failed socially and environmentally, if not economically, we are taking a critical approach to their emergence, which is important to working out what really makes for best practice as opposed to just greenwashing.

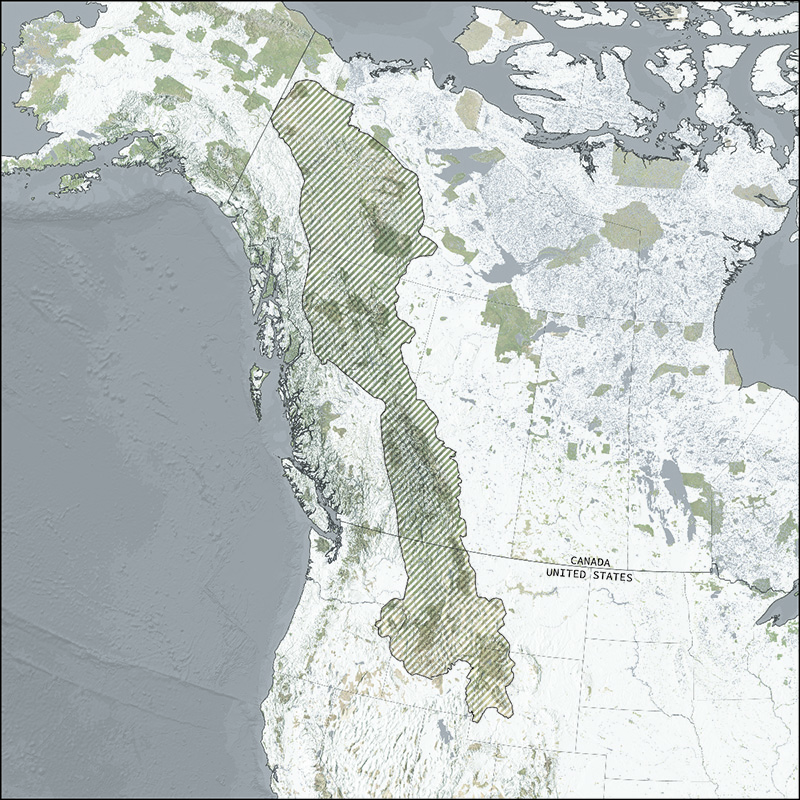

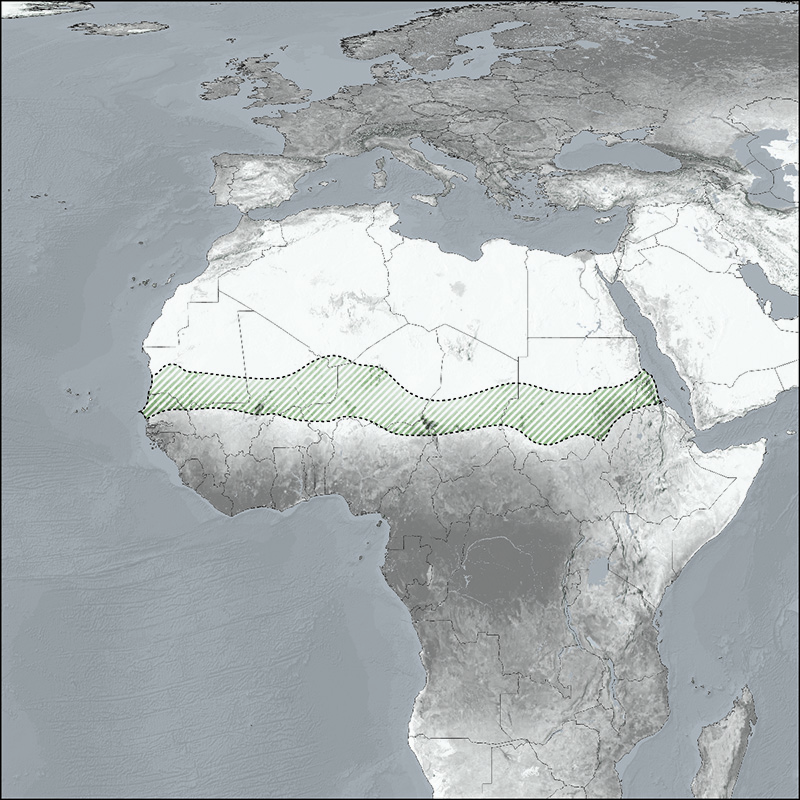

I mean there are great projects like the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative and the Great Green Wall across Sub-Saharan Africa, but when someone like President Trump endorses planting trillions of trees, you have to wonder what’s really going on.

The Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller

The Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller  The Great Green Wall. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller

The Great Green Wall. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller Whereas the definition of old school megaprojects was always financial -- say over a billion dollars -- our working definition of Mega-Eco Projects is not numerical. Rather, it is that they are “complex, multifunctional, landscape-scale environmental restoration and construction endeavors that aim to help biodiversity and communities adapt to climate change.”

Furthermore, unlike the old concrete megaprojects, Mega-Eco Projects use living materials; they cross multiple site boundaries, they change over time, and they are as much bottom up as top down. The project narratives are also different, whereas megaprojects were always couched in terms of modern progress and nation building, the Mega-Ecos are about resilience, sustainability, and a sense of planetary accountability.

There are four categories of Mega-Ecos. The first are large-scale conservation projects; the second are projects that seek to resist desertification; the third are watershed plans; and the fourth are green infrastructure projects in cities either dealing with retrofitting existing urbanity or urban growth.

As you would expect, landscape architects tend to be involved with this fourth category, but there is a bigger future for the field in the other three, which is part of our motivation for studying them.

By our current assessment, there are about 40 Mega-Eco Projects taking place in metropolitan areas around the world today. These tend to be in the global north and China, notably the Sponge Cities initiative, where so far over $12 billion has been spent in 30 trial cities. We have not yet conducted a comparative analysis of these projects, nor are many of them advanced enough to yet know if they are, or will be, successful.

With specific regard to urban biodiversity, I don’t think there is yet a city in the world that really stands out and has taken a substantial city-wide approach that has resulted in design innovation. It will happen. As they do with culture, cities will soon compete to be the most biodiverse. The conception that cities are ecosystems, and that cities could be incubators for more than human life is a major shift in thinking, and while landscape architecture has a strong history of working with people and plants, it has almost completely overlooked the animal as a subject of design. That said, we shouldn’t romanticize the city as an Ark or a Garden of Eden. The city is primarily a human ecology, and the real problem of biodiversity lies well beyond the city’s built form. Where cities impact biodiversity is through their planetary supply chains, so they need to be brought within the purview of design.

Singapore is a case in point. Because it developed the Biodiversity Index, Singapore has been able to tally its improvements with regard to urban biodiversity and tout itself as a leader in this area. Many other cities are adopting this tool and this is good.

But this is also where things get tricky, because whatever gains Singapore can afford to make in its urban biodiversity need to be seen in light of the nation’s massive ecological footprint.

I mean, Singapore can make itself into a garden because the farm and the mine are always somewhere else. I would call Singapore a case of Gucci biodiversity, a distraction from the fact that they bankroll palm oil plantations in Kalimantan, the last of the world’s great rainforests.

That said, every city is shot through with contradictions. The question then is to what degree do the designers play along or whether they can make these contradictions the subject of their work, as opposed to its dirty little secret. The Gardens by the Bay project, for example, is a brilliant case of creating a spectacle and keeping tourists in town for an extra day, but it’s got nothing to do with biodiversity beyond the boundary of the project.

Gardens by the Bay, Singapore / istockphoto.com

Gardens by the Bay, Singapore / istockphoto.com

The late E.O. Wilson and other biologists and ecologists have also called for protecting half the Earth’s lands and oceans. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) split the difference in their recent report, calling for 30-50 percent to be protected. What are the extra benefits to protecting 50 percent? What does this mean for the planning and design of existing and future human settlements?

I’d trust E.O. Wilson or better still, James Lovelock, with the calculation for a healthy planet, but the dualism of humans here and biodiversity over there that tends to come with Wilson’s notoriously puritanical position is problematic.

The world is a novel, highly integrated, human dominated ecosystem, and design has to work at improving the symbiotic nature of that condition. Each site needs to be assessed on its own biological and cultural terms as to what can be more deeply integrated or what should be separated out; what has to be actively curated and what can be left to its own devices. As Sean Burkholder and others have pointed out, this means designing time as well as space.

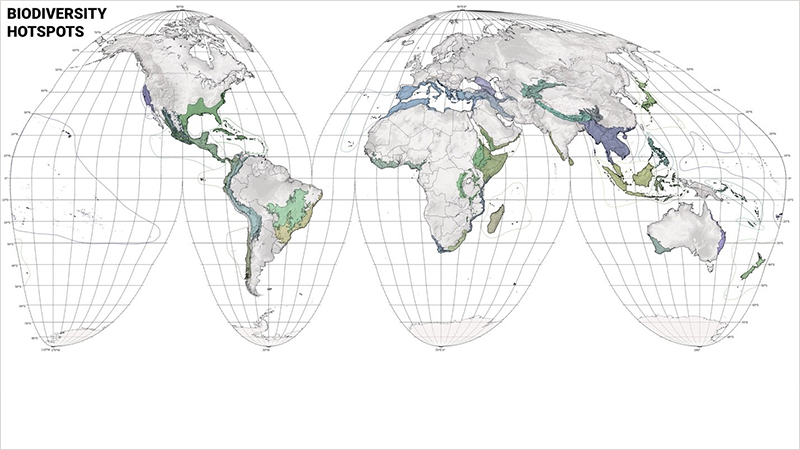

The thing with Wilson is where exactly would his 50 percent be? He never really explained it in spatially explicit terms. Half Earth means another 34.5 percent on top of what we currently have protected. As a priority, it would have to comprise any unprotected forest or other areas of remnant vegetation and whatever can be clawed back in the world’s biodiversity hotspots.

The World’s 36 biological hotspots. Image by Rob Levinthal. Courtesy Richard Weller

The World’s 36 biological hotspots. Image by Rob Levinthal. Courtesy Richard Weller

But the numbers don’t really add up. About 40 percent of the Earth’s ice-free earth is currently used for food production, 30 percent is desert, and 30 percent is forest – although “forest” is a loose term, and some of that already overlaps with protected areas. Given that the global foodscape is and will probably continue expanding, 30 percent total protected area seems more reasonable than50. It is my belief that design, if given the chance, can weave viable biodiversity through the contemporary agricultural landscape whilst maintaining overall yield.

Even 30 seems a stretch, because if you project the expansion of crop land by 21st century population growth, we need most of the planet to feed people, so something has to give. Either we massively increase yields from the current agricultural footprint or biodiversity gets pushed further into the mountains. Or billions starve.The prospect of us reducing the planet to a monoculture is very real and very scary on every level.

To your question, the benefits would be that by more or less doubling the current conservation estate, we could create larger patches in the hotspots and seek to achieve connectivity between the existing fragments of protected areas. As landscape ecology teaches, it is only with larger patches and substantial connectivity that we can create a truly resilient and healthy landscape. The problem is of course that the patches and corridors have to be reverse engineered into hostile territory. Human settlements and agriculture have to make way for larger patches and greater connectivity and planned around it. To turn the whole thing on its head, human settlements and human land uses have to protect the global conservation estate. Easy to say.

Biodiversity loss is often considered a result of the climate crisis. But there are other issues also driving increased biodiversity loss and extinction rates worldwide, such as increased development in natural areas, the spread of transportation systems, and pesticide and chemical use. How do explain the relationship between climate change and biodiversity loss?

When people hear “biodiversity” they almost invariably think of charismatic megafauna, but as you indicate, the problem runs deeper and at a much finer grain. Of course, we are now obsessed with chasing every carbon molecule, but for life on and in the land and its waters, the problem is also excess manufactured nitrogen along with other toxins. Ironically, despite ultimately killing microorganisms upon which soil health depends, industrialized fertilizers have slowed the rate of deforestation that would have occurred had the world tried to feed itself without industrial fertilizers because they have, at least in the short term, increased yields.

The main problem from a spatial planning and land use perspective is that species increasingly need to migrate so as to adapt to a changing climate but they find themselves trapped in isolated fragments of protected areas or stranded in unprotected scraps of remnant habit.

There is another part of this though, and that is that the entire discourse and politics of environmentalism is couched in terms of loss. But a truer picture perhaps is that as ever in the chaos of evolution, there will be winners as well as losers. I don’t think we know what is really happening or what will happen, so in that sense we need to design landscapes as insurance policies, as expressions of the precautionary principle where we just try to maximize the potential of life to evolve. In this regard landscape architectural research and design becomes less about finished projects, and more about conducting experiments based on both scientific and cultural questions related to biodiversity.

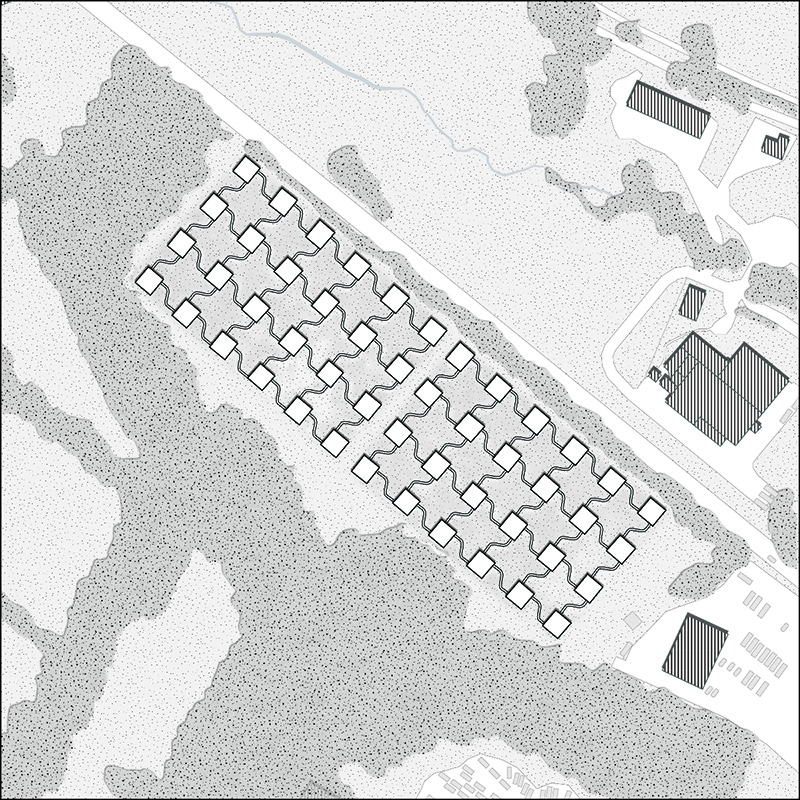

The Metatron at the Theoretical and Experimental Ecology Station in Moulis, France is a good example. The Metatron is an experimental field of 48 enclosures in which species composition, temperature, light and humidity can be controlled. Each enclosure is connected to the others via small passages that can also be controlled. In this way, the Metatron is a simulator of landscape dynamics, a model microcosm in which each enclosure is understood as a “patch” and each connector a small simulation of a landscape “corridor.” Since 2015, given the limitations of its size, experiments have focused on studying how small species like butterflies and lizards move through the system, but many more species could be studied using a similar system at larger scales. In essence, the Metratron is learner’s kit, helping us understand how best to reconstruct landscapes at scale.

The Metatron. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller

The Metatron. Drawing by Oliver Atwood. Courtesy Richard Weller

Your own research, including the ASLA-award winning Atlas for the End of the World, documents how areas at the edge of sprawling cities around the world are increasingly colliding with biodiversity hotspots, which are defined as highly valuable reservoirs of diverse and endemic species. What are the implications of your research?

By conducting an audit of land use and urban growth with regards to CBD targets in the world’s biodiversity hotspots, the Atlas set the scene for my two current research projects.

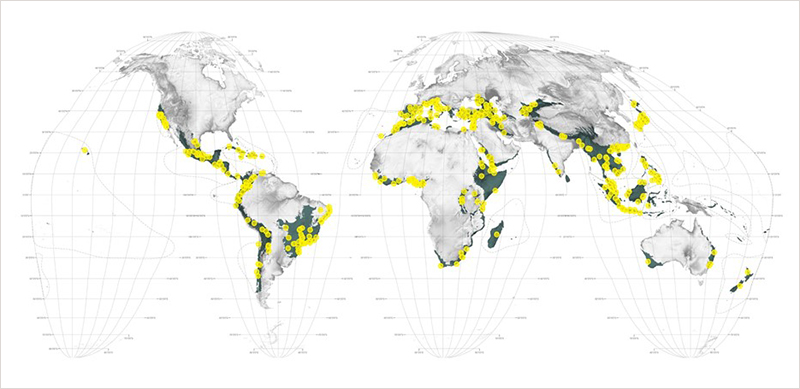

The first is the Hotspot Cities Project and the second is the World Park Project. A hotspot city is a growing city in a biodiversity hotspot – the 36 regions on Earth where endemic biodiversity is most diverse and most threatened. We’ve identified which of these cities —over 90 percent— are sprawling on direct collision courses with remnant habitat harboring endangered species.

Hotspot Cities: Each yellow dot represents a city growing in direct conflict with endangered species. Image by Chieh Huang. Courtesy Richard Weller

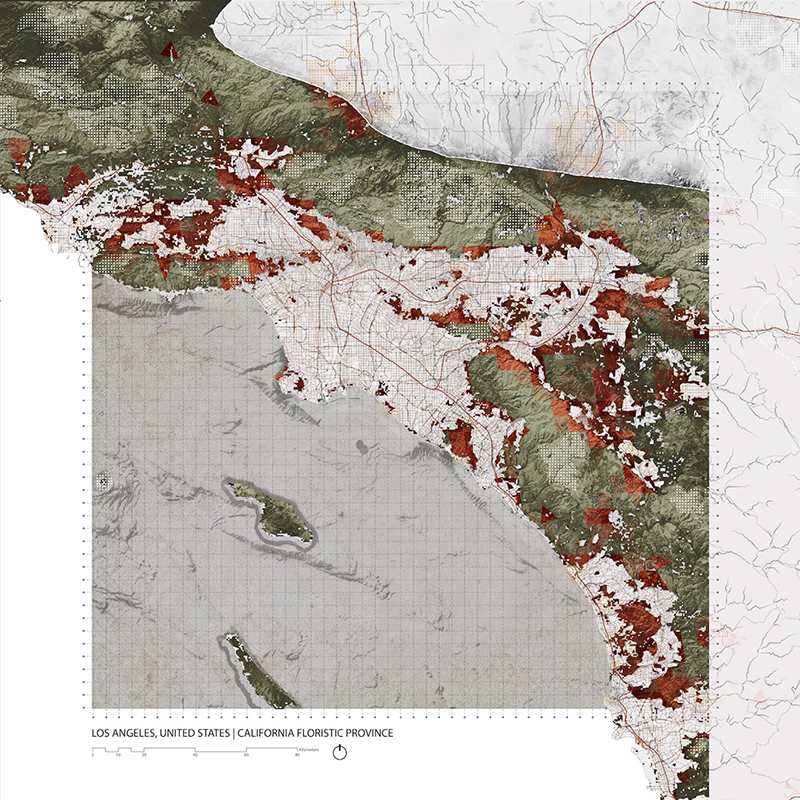

Hotspot Cities: Each yellow dot represents a city growing in direct conflict with endangered species. Image by Chieh Huang. Courtesy Richard Weller  Los Angeles in the California Floristic Province biodiversity hotspot. Red areas indicate conflict between growth projected to 2050 and the range lands of endangered species. Image by Nanxi Dong. Courtesy Richard Weller

Los Angeles in the California Floristic Province biodiversity hotspot. Red areas indicate conflict between growth projected to 2050 and the range lands of endangered species. Image by Nanxi Dong. Courtesy Richard WellerIn our mapping we identify the conflict zones between development and biodiversity and then we conduct design case studies as to how the conflict could be mitigated. The argument is that destructive sprawl is not a fait accompli, and designers—especially landscape architects skilled in urban design— can create credible alternatives by taking a holistic, city-wide perspective. This research especially draws attention to peri-urban landscapes that are largely overlooked by the profession, because the design dollar has mainly been invested in city centers.

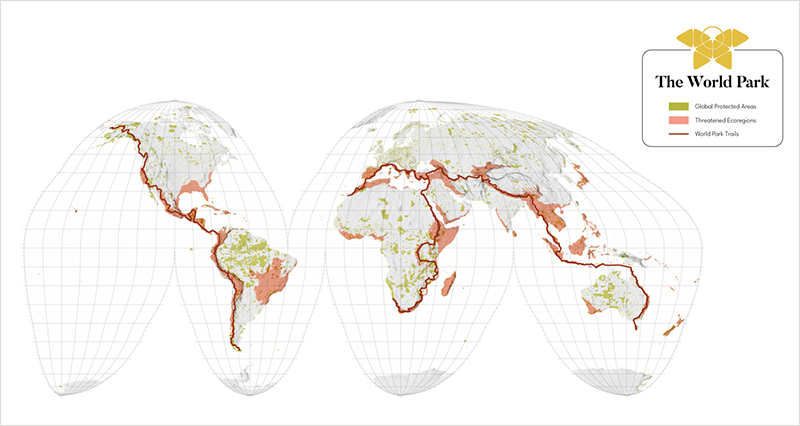

The World Park Project is a big vision for a new form of conservation landscape, one that actively involves humans in its construction. It’s an answer to the question of where those 150,000 Central Parks should be, as I mentioned earlier.

The idea of the World Park begins with the creation of three recreational trails: the first from Australia to Morocco, the second from Turkey to Namibia, and the third from Alaska to Patagonia.

Passing through 55 nations, these trails are routed to string together as many fragments of protected areas in as many hotspots as possible. The trails are catalysts for bringing people together to work on restoring the ecological health of over 160,000 square kilometers of degraded land in between existing protected areas.

In this way, the Park is about building a coherent and contiguous global network of protected area. It addresses the two biggest challenges facing global conservation today: ensuring adequate representation of biodiversity in protected areas and connectivity between those areas. It sounds crazy, but forging connectivity at this scale is just what we do for every other form of global infrastructure. Humans build networks, and it’s high time to build a green one.

The World Park Project: 3 trails through biodiversity hotspots at a planetary scale. Image by Madeleine Ghillany-Lehar

The World Park Project: 3 trails through biodiversity hotspots at a planetary scale. Image by Madeleine Ghillany-LeharI was expecting derision from design academics about World Park, because “going big” is generally seen as neo-colonial or megalomaniacal. I was also expecting world weary eye-rolling from the conservationists or outright rejection of the idea because it would suck the oxygen out of their own efforts, but generally the reaction has been very positive.

Most people, particularly in the NGOs, have reacted like “wow – this is exactly what we need right now.” They know they can’t just keep adding more fenced-off fragments of protected area to meet UN targets. There are now so many conservation efforts going on but they are all disconnected from one another. A World Park could galvanize these efforts into something that is greater than just the sum of its parts.

In any event, my research team (Alice Bell, Oliver Atwood and Elliot Bullen) have completed the mapping of the Park’s territory. Now I’m talking with UNESCO about how we might move the idea to a proper feasibility study. Realistically, nothing will happen unless the major NGOs adopt it, along with some philanthropic champions and the relevant ministers in those nations whose sovereign territory is involved.

Only half-jokingly, I think Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Richard Branson should bring their toys back to earth and take this on. Musk could fund the African trail, Bezos the Americas, and Branson would pick up the Australia to Morocco piece. At current landscape restoration rates, I worked it out at about $7 billion.

That’s an expensive park, but the better question to ask is not what it costs but what is it worth? For a mere $7 billion a World Park could provide investment in impoverished landscapes. It could provide meaningful experiences and jobs for lots of people. Above all, it would be a profound sign of hope that humanity can work together to be a constructive force of nature instead of its executioner.

Lastly, how can landscape architecture academics and practitioners better partner to address the twinned biodiversity and climate crises? What additional research is needed to better weave biodiversity considerations into broader climate solutions?

Well, as someone who has spent a lifetime in both the academy and practice, I would really like to take this opportunity to attest to the value of both. I think it’s a problem that the academy demands young faculty have PhDs but not necessarily any practice experience. Just as I think it’s a problem that certain elements of the profession become anti-intellectual over time and associate this with being savvy professionals.

Academics have the luxury of formulating research questions and methods, whereas practitioners are generally making it up on the run and learning by doing. These are both entirely valid ways of forming knowledge, and they actually need each other.

My work over the last decade has been very big picture, but it means nothing unless it can translate into design. So I think there are two forms of design needed right now with regard to biodiversity and they both bring academics and practitioners together.

The first is taking on a whole-of-city scale and considering the city as an incubator and protectorate for biodiversity and offer plausible scenarios as to how the city’s growth can be best managed to minimize negative impact on existing biodiversity. Until city authorities pay properly for this work, the academics have to act as the start-ups. They can form interdisciplinary teams to find research funding to do this work, preparing the way, as it were, for practitioners to come in and realize specific projects.

Which brings us to the second form of design -- the project scale. Take any project at any scale and ask how to approach it if your client was every living thing, not just humans, and then work as if your life really depended on serving all of them – which, incidentally, it does! To answer this takes both time and levels of knowledge beyond landscape architects irrespective of whether they are in the academy or in practice. We are very accomplished at designing for humans but still have everything to learn if we consider biodiversity as our client.

In terms of both professional and academic practice, the role of the landscape architect, now more than ever, is to bring the world of development and the world of conservation together over the same maps and serve as a negotiator.

It sounds like a platitude, but it goes to the core of our job description, and it’s never been more important. There has never been more at stake.

Richard J. Weller, ASLA, is the Meyerson Chair of Urbanism and Professor and Chair of landscape architecture and Executive Director of the McHarg Center at The University of Pennsylvania. He is author of seven books, including the forthcoming The Landscape Project, a collection of essays by the faculty at the Weitzman School of Design. He is also the creative director of LA+, the interdisciplinary journal of landscape architecture. In 2017 and 2018, Weller was voted by the Design Intelligence survey as one of North America’s most admired teachers and his research has been published by Scientific American and National Geographic and exhibited in major museums around the world.