News

Interview with Patricia O'Donnell, FASLA

Patricia O'Donell, FASLA / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

Patricia O'Donell, FASLA / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

Over your career, you've worked on more than 500 cultural

landscape projects. You have highlighted Pittsburgh’s $124 million

investment in revitalizing its public spaces, such as the Mid-Century Modern

Mellon Square, which you restored, as a model. What does Pittsburgh know that

perhaps other cities need to learn?

In the 19th century, Pittsburgh had a vision of setting aside major

green spaces in order to shape the city. Neighborhoods grew up around the

green spaces. Since Pittsburgh is still today a neighborhood-based city,

everyone cares deeply

about their green assets. Pittsburgh has a history

of understanding the value of parks.

Pittsburgh looked at their historic parks and said,

“This has value for the city." The revitalization effort was initiated by the very

bright Meg Cheever, a lawyer by education and a publicist by application who founded the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy. She knew she needed to grab attention so she built up the Conservancy as a real partner to the city. She was

very savvy about not having an adversarial relationship with the city, instead creating a true partnership. We've worked in a number of conservancies, and

that coin can flip both ways. The first thing is you need to be a partner; the

second thing is you have got to recognize value.

When I started my firm in the late-80s, we did a project in Gilford, Connecticut. I told them there are four groups of tools for improving the public realm:

community engagement, plans or advisory tools, law or regulation, and

finance. As landscape architects, we're good at community and planning, not necessarily so good at legislation or

finance. If we recognize those are the four

things we need, we can figure out who to partner with and what skill

sets and mindsets are needed to move forward.

Pittsburgh started with its 19th century legacy. They had three big parks: one that was gifted to the city in the early 20th century

by Henry Clay Frick; Mary Shenley’s property, which the city had bought and then added to Shenley Park; and Highland Park, which

was around a reservoir and then grew into a park. So each park had a

different vector. Then, they focused on the Mid-Century Modern pieces: The Point and

Mellon Square, which were the two iconic public spaces built in the 50s and part of the first Pittsburgh Renaissance. Those spaces became elements of a national model for urban renewal.

They knocked down 25 percent of the core of the city in a 10-year period and

rebuilt it.

Restored Mellon Square, Pittsburgh, originally designed by John O. Simonds / Ed Massery

Restored Mellon Square, Pittsburgh, originally designed by John O. Simonds / Ed Massery Restored Mellon Square, Pittsburgh, originally designed by John O. Simonds / Jeremy Marshall

Restored Mellon Square, Pittsburgh, originally designed by John O. Simonds / Jeremy Marshall

Now there's good and bad there. There was some environmental

injustice and other problems, but they also renewed the

core of the city and rebranded Pittsburgh. A number of other cities

followed that path of renewal. (We called it urban renewal but often it was

urban destruction). But the initiative worked for Pittsburgh. They were able to lift up what was a gritty steel city

where industrial workers had to bring a minimum of two shirts to

work because the air quality was so bad.

Your

firm, Heritage Landscapes, partnered with HOK on the restoration of the National

Mall in Washington D.C. What was involved in that process?

We were asked by the National Park Service (NPS) to track the history of Mall, which they framed as from L’Enfant's 1792 plan to the present. The NPS asked us to framed it by the plans, but the plans did not reflect what the Mall actually was. We carried out this project as part of a NEPA compliance process.

Through a mapping effort, we overlaid all the soil disturbance over time -- deep subsurface, shallow subsurface, surface -- in CAD and made this very fun color map that showed probably a couple of teaspoons of the Mall were not

altered over time. While we met NEPA compliance, we also now had the background, understood what the design was, and how the design of

the Mall evolved to what we love today.

That evolution happened because of the strength of the personality and the stature of Frederick Law

Olmsted, Jr.. He served on the McMillan Commission, the Commission on Fine Arts (CFA), and what is now called the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission (NCPC). He persuaded the NPS to do the plan for the Mall. The linear quality of the green panels was key.

We focused the HOK team on getting the grading right. The Mall had been

slightly domed and tipped northward because the Tiber Creek and the Washington

Canal -- the drainage -- were to the north. The Capitol, the White House and the Smithsonian were set on three

hills, and so the Mall, the space in between, was kind of mushy. The new shape of the Mall needed

to respond to that topography. The original lawn panels had a vertical curve to help drainage.

The NPS wanted the new panels accessible, under

a five percent grade and, if possible, under two percent. We had to balance access,

sustainability, and history. In addition, the soils were as hard as concrete. And as a result, the most common plant was a

small knotweed. Soil experts, James

Urban, FASLA, and others, and I thought that grading it under 2 percent wouldn't work. The lawn panels would continue not

drain well and tend toward compaction. We got the NPS to go with at

least 1.8 percent, but at the edges we were up at about 4 percent and then 3 percent and then

domed, but tipped northward.

To reduce compaction, soil must have open air pores. The team found the best soil for defending against

compaction is sandy loam. Investigations addressed whether or not

there should be additives in the soil; these little crunchy things that spring

back and keep the soil open. The NPS didn't want to go down that road, so they approved a very good sandy soil mix. The

first phase they decided they had a little too much organic matter. They

changed it up a little bit on the second phase. We achieved what L’Enfant and Frederick Olmsted, Jr. were after: the long green corridor.

Restored National Mall, Washington, D.C. / Adam Fagen, Flickr

Restored National Mall, Washington, D.C. / Adam Fagen, FlickrYou just completed a cultural landscape

report for Woodstock and have begun design work to reinterpret the landscape,

so its story becomes more accessible to future generations. What did you unearth

through your research? Where has that led your planning and design work?

The Woodstock project is a lot of fun because it’s such recent history.

We developed the Cultural Landscape Report by looking at the

main field where the concerts happened. We found information digging into the

archive at the Museum at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. They had been gathering material for years, including all these low-flown, oblique aerials from a plane and ground photography.

It turned out that just barely

digging into the research we found the envelope is a lot bigger. There's the main field, Filippini Pond, where everybody went skinny dipping, and Bindy Bazaar in the woods between the main field and the hog

farm where food was made. The hog farm tells the story about the commune movement. They provided the food at

Woodstock, so everyone saw how a commune worked.

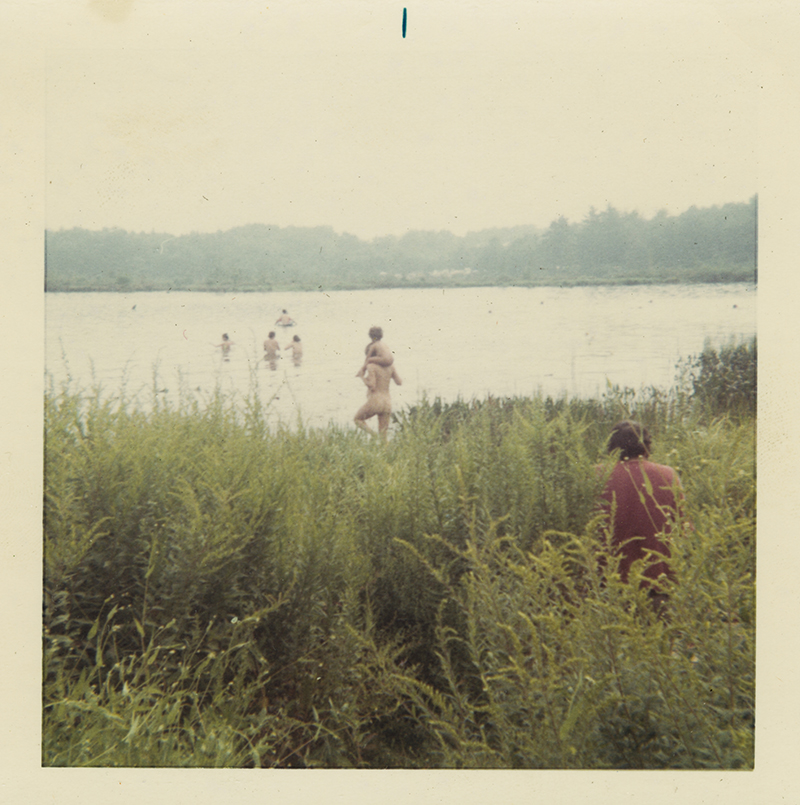

Hippies enjoying Filippini Pond / C. Alexander, 1969, Bethel Woods Archive

Hippies enjoying Filippini Pond / C. Alexander, 1969, Bethel Woods Archive

In opening up

the land base envelope, we compared what we saw being used to what was

actually leased to the concert organizers by the farmer Max Yasgur. The event was held on an alfalfa field, which was mown

for the event. I happen to have an old alfalfa field and know what they look

like. So when I saw the photos, I thought: “Oh, this is an old alfalfa

field with people in Indian prints striding across it.”

There was a guy in one of the trailers who was drawing

plans. He drew one plan of the Bindy Woods with the trails, so we used that to figure out that interesting area. Hippies had set up

20 something booths to sell tie dye, Indian prints, roach clips, or

whatever. They put up hand-painted signs on the trees naming the paths -- highway groovy path, etc.

Woodstock's organizers planned very well for 100,000 people. They had medical officers and police; they were actually well-organized. But when the crowd hit 400,000 or 500,000, they didn't have enough bathrooms or food.

The cultural landscape report investigation has informed where design interventions might be. The stage configuration was very interesting. The 60 by 70-foot stage was warped because of the plane of the slope of

the hill. They made a turntable so they could swing the acts. When it

rained, the platform wouldn't turn anymore. They never finished the fencing but had

this gorgeously shaped batwing fence.

Woodstock stage and batwing fences amid the crowds / Pinterest

Woodstock stage and batwing fences amid the crowds / Pinterest

We developed schematic designs of

the footprint of the stage; the batwing fence; the performers'

bridge, which went over the road; and the posts at the height where the bridge

occurred. We have a series

of design options in front of the client that are very fun. We've already started to

build the Bindy Bazaar paths and signs to interpret the vendors.

Bindy Bazaar paths and signs / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

Bindy Bazaar paths and signs / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and PlannersWhat makes a successful cultural landscape report? How are these reports evolving?

When we started doing cultural landscape reports, they were

called historic landscape reports. There weren't rules. We sat on committees and helped frame cultural landscape preservation and

management standards and guidelines for the National Park Service and Secretary of Interior. There are a set of steps: history, existing landscape condition, analysis of continuity and change, treatment exploration and recommendations. The goal is to find out if you are going to just preserve a landscape as-found,

restore it to some earlier documented time;

reconstruct missing pieces; or rehabilitate the landscape, adapting to current needs. These reports help us to suit contemporary and future needs while preserving what has been inherited.

We're now up to over 110 cultural landscape reports or assessments. The New York Botanical Garden and Longwood Gardens

really wanted the history because they sought to understand how their property had

evolved. That was all they wanted. So sometimes it’s

just a piece. When we worked at Dumbarton Oaks, they wanted analysis as well,

so they could understand continuity and change, the evolution of

the designed landscape of Mildred Bliss and Beatrix Farrand.

Bloedel Reserve asked for a heritage landscape study. They came to us and said: “We understand Prentice Bloedel’s words, but what do they mean?” And we said, “You have the artifact. We can

interpret the artifact to get at the meaning.” Cultural landscape reports are customized for each place. For the second phase of analysis at Bloedel, we told them: “Okay, now you actually

need to dig deeper." They have an amazing landscape that has four character areas and 26 component landscapes. The genius of this landscape is the

differentiation between the individual components, but part of

the practices they were employing in their daily management were blurring those

unique aspects. We helped them really hone in on the character of the moss

garden versus the Japanese garden versus the woodland paths so they can manage by area.

Bloedel Reserve / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

Bloedel Reserve / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

For our work at Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village, we made sure we researched the African American contribution to shaping the landscape. This kind of analysis depends on the place and the client, but

there is a heightened sense of social justice today. That framework led us to understand whose labor

actually created a place. At the Academical Village, we found the way of life for enslaved peoples did not change after the

Civil War. What changed their way of life was technology. When water and sewer systems were connected to every building and lighting

came, the daily life within the core of the campus

shifted. These changed the back breaking labor of daily life -- hauling water,

chopping wood, and gardening -- by enslaved peoples, who were

freed at that point, but whose life and daily activities had not substantially

changed from the evidence we saw on the land.

University of Virginia / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

University of Virginia / Heritage Landscapes, LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners

You have said that "culture and nature are entangled and inseparable." How did

you reach that conclusion?

While we have

protected areas on the planet, there isn't place on Earth that hasn't been influenced by humanity. We're in an era of human influence if you look at climate change and, hopefully, our greenhouse gas draw down vectors. If we

envision ourselves as a part of nature, and we see humanity as one

species of many, rather than the dominant species, and we see the planet as the

place where we all live, it changes our perspectives on how to proceed. Nature and culture, place and people are completely interconnected,

interrelated, and interdependent.

The big issue with climate change is finding ways to draw down. I was fascinated with Paul Hawkins’ book Drawdown, which outlined the top hundred ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Most people would think the answer would be more solar energy or carbon

sequestration. But society needs to get up to speed with

its needs. Actually, some of the most effective carbon reduction solutions are the empowerment of women, education for girls,

and birth control for women, so we don't overpopulate the world, and women can take a real role in the future.

You've

been a strong advocate for cultural landscape preservation, equitable access to

public spaces, and inclusive planning and design in international organizations such as

UN-HABITAT, UNESCO, and ICOMOS. At the same time, you have also advocated for

greater landscape architect participation in these organizations. How can we

bridge the gap between policy bodies and the design world?

I have had rewarding engagements with

peers and related professionals in working groups that build international

doctrine. You gain a broadened sense of where your

work can fit because the picture is expanding for you. In my opinion, all of

us can benefit from global engagement -- from meeting with peers face to face and engaging in committees to participating in the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA), which has a very strong new

policy that they passed in September on climate change, and ICOMOS, which is a curator of world heritage,

the culture advisor to UNESCO World Heritage. I am constantly contributing to ICOMOS to strengthen our global heritage.

In these international bodies, I learn from others, share

what I know, and the result is we all lift ourselves up together. We also bring forward emerging professionals. I’m currently the president of the

ICOMOS-IFLA International Scientific Committee on cultural landscapes.

We have about 212 members worldwide. We're strengthening and coalescing

our membership in Latin America to do a better job there with cultural

landscapes. We're adding a number of emerging

professionals to begin to address the wealth of cultural heritage in Africa. We gain a lot by uplifting everyone, all boats rise together.

Patricia O'Donnell, FASLA, AICP, Fellow, US/ICOMOS, is founder of Heritage Landscapes LLC, Preservation Landscape Architects and Planners, winner of the ASLA 2019 Firm Award. Her works and contributions sustain and revitalize our shared commons of public historic landscapes and advance the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 2030 Agenda, and the New Urban Agenda.

Interview conducted by Jared Green at the ASLA 2019 Conference on Landscape Architecture in San Diego.