News

Interview with Janet Echelman

Janet Echelman / Todd Erikson

Janet Echelman / Todd Erikson

What is your role as a public artist today? Are you here to enliven dead places, create a new sense of place, or just get us to feel something new?I am engaged in enlivening dead or invisible places. I'm drawn to places that somehow do not yet click, because it's a challenge -- enigmatic and interesting. The hardest thing is to go make art in a place that's already good.

Creating a new sense of place is a very interesting problem for me in my practice of public art. I often think of it more as creating a sense of place, because many of these places felt anonymous before. I'm often part of a larger effort that involves a landscape architect, architect, and urbanist.

Feeling something new: Yes, I am interested in that because it's about feeling alive in the moment to encounter, experience, absorb, just see the world in a different way. My work is dynamically changing in different weather and at different times of year, which is actually very in-tune with landscape architects' sensibility. I admire landscape works that have plants that flower or drop their leaves at different seasons, the sense of sculpting something that has seasonal change.

What kind of spaces best enable us to interact with your voluminous, floating artworks? When you're installing a piece in an existing park or plaza, how do you see a spot and say to yourself: Yes, that'll work?

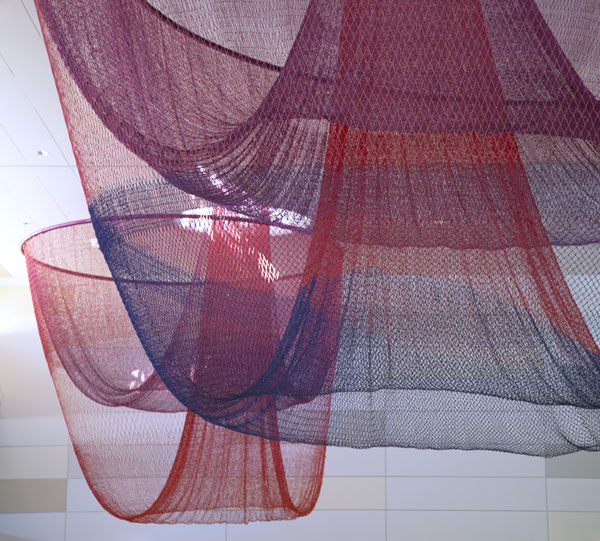

I've created sculpture in a forest, in fields, and on a beach. These are very satisfying environments, but there is no more compelling site than the middle of a city where people are. These works are about the experience of how it feels to be underneath them. The reason I make them is because I want to be under something like this.

I don't know if my work is a landscape, but they're a scape of sorts.

They're an environment that you go inside of, and they're often

integrally linked with a landscape beneath them. Maybe they're a

skyscape?

When I am brought in to work with a team, it's a question of understanding what the options are, walking through the site, thinking about the patterns of pedestrian movement, and where there might be a place of contemplation. Where is a place where people can lie down and look up?

She Changes, Porto, Portugal / Enrique Diaz

She Changes, Porto, Portugal / Enrique Diaz

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, your recent piece for the 30th anniversary TED conference in Vancouver, was imbued with technology that enabled the public to interact. What was your motivation for this interactivity? Does this mean we can only reach people through their smartphones now?

Each project I take on has to have some edge where I'm experimenting or pushing limits. In this project, I wanted to give the public a way to interact with color and lighting. It was a collaboration with a digital artist Aaron Koblin, who leads Google's data art labs.

This piece is about social gathering in cities. Its form is derived by 2,000 years of urban history and the city of Rome, when the Colosseum was built. The Colosseum once had a textile work suspended by ropes called a velarium. We don't know exactly what it looked like, but this was my challenge to create a velarium for today. I was thinking about why people gathered in Rome 2,000 years ago to watch violent spectacles and why we gather today.

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, Vancouver, British Columbia / Ema Peter

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks, Vancouver, British Columbia / Ema PeterAaron and I spoke how often technology connects us to all sorts of people but never the person standing next to us. In the context of the sculpture, it would not only connect you to your friends list but the person physically next to you. We were using technology as a tool to bring people together; it was both a physical space and a virtual space at the same time.

It's not the phone that distances us. I don't feel that the smart phone has to control us in terms of how we relate. We can use it in a way that brings us together in a real landscape in real time in a real conversation.

You partnered with landscape architecture firm OLIN on Pulse, an exciting project coming to the new plaza in front of City Hall in Philadelphia. Can you talk about the collaborative design process with them and the other designers, engineers on the team? What did you learn from them and what did they learn from you?

The project in Philadelphia with OLIN is a completely

different experience for me, because it's not about looking up. It's in front of the beloved historic Philadelphia City Hall. It was more about working

together with the landscape architecture to engage people and add playfulness. It's meant to engage above ground with what's going on underground.

It was an intimate collaboration. We'd have the site model with trace paper. I would draw a line, and Sue Weiler, FASLA, a partner with OLIN, might pick up the pencil and complete the line. OLIN was open and willing to invite me into the landscape, to join in what became a completely integrated work of art and landscape. With landscape architects, the projects tend to become really

collaborative. Neither side is really too attached to their ideas.

That's not always the case when collaborating in the design world.

Sometimes, there's an uncomfortable butting of heads.

Their input really changed what I designed in the end, because I was initially thinking about being vertical and engaging with the parkway, which is on the diagonal. The more I learned from the OLIN team, the more I saw it was as about people moving through this plaza. I became engaged with the ground plane in a way I never before. The project required me to delve into the history. The site housed the original waterworks of the city, the former railroad station of the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Broad Street Station, where trains ran on steam. So I developed a completely new material to engage with this history, working with mist or fog as a sculpture material and colored light, to bring the sense of the trains.

Pulse, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania / OLIN

Pulse, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania / OLIN

Having your pieces in so many different types of landscapes, you must have some sense of what landscape architecture works and doesn't work. Is there an ideal relationship between landscape architecture and public art or is it all relative?

The only way I know if a landscape is working is my subjective experience. How do I feel when I walk through a space? In a former phase of my life, I worked as a psychotherapist. In the training, they talked about self as instrument. How you feel is your greatest tool in understanding what's going on around you. That training has helped me as an artist working in the public realm collaborating with landscape designers. So it is subjective, but it is in fact my only tool, so that's how I judge a space.

I can't say what is the ideal relationship between public art and landscape, but I am intrigued where they are in conversation with one another. Many of my works are in the sky and they talk to the landscape. I lived in Bali and there they say, "The sky is my father, and the Earth is my mother." It's a romance between the ground plane and the sky.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands / Janus Vanden Eijnden

Amsterdam, The Netherlands / Janus Vanden Eijnden If you have to deal with the legacy of bad planning or landscape architecture, how can you fix it?

It's interesting what I am asked to fix. At the San Francisco Airport, they asked me to create a zone of re-composure for people after they clear security. In cities and even on campuses, I'm asked to create a "heart." This is a challenging but worthy goal. I can never reach my ambitions, but I'm willing to be aspirational.

Every Beating Second, San Francisco Airport / Becky Borlan

Every Beating Second, San Francisco Airport / Becky BorlanI am frequently part of a team that includes landscape architects who are addressing a fix to some previous plan, often the result of urban renewal. We're in a moment when we are finding many of the designers in the 60s and 70s may not have succeeded in creating what we all want.

For example, Boston had an elevated highway going through the middle of it. With the "Big Dig," they were able to remove that. The highway was a mistake of an earlier era where the automobile was given a precedence over the pedestrian. With my new project coming in, I'm part of the process of bringing this place back to the people.

Your hit TED talk, which has been viewed more than a million times, is all about the rediscovery of wonder. What advice do you have for designers trying to keep in touch with that feeling, given all the challenges involved in designing and building something these days?

I try to keep a sense of wonder in my own life and practice. I try to hold a space of time to experiment, as a kind of research. In the business world, successful companies have R&D labs, but we artists and designers rarely have that benefit. We must reserve a space for discovery and wonder.

Janet Echelman builds living, breathing sculpture environments that respond to the forces of nature — wind, water and light — and become inviting focal points for civic life. She is recipient of the Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Her TED talk, “Taking Imagination Seriously,” has been translated into 34 languages and is estimated to have been viewed by more than a million people.

Interview conducted by Jared Green.