Criminalized for Their Very Existence: The Spatial Politics of Homelessness

Award of Excellence

Research

Skid Row, Los Angeles, California, United States

Jared Edgar McKnight, Associate ASLA

Faculty Advisors: Katy Foley; Hyunch Sung

University of Southern California

This project did an excellent job of citing policy and specific laws that are relevant to tackling the ways we have regulated and policed people experiencing homelessness. It is generous with references and a clearly defined scope of research. The proposition is comprehensive and elegant and provides space for continuity—we also loved the way the project took shape as a visual activity where information is presented, interrogated, condensed, and synthesized.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Jerome Chou

Faculty Contributor

Lauren Elachi

Faculty Contributor

Los Angeles LGBT Center

Engagement Collaborator

Project Statement

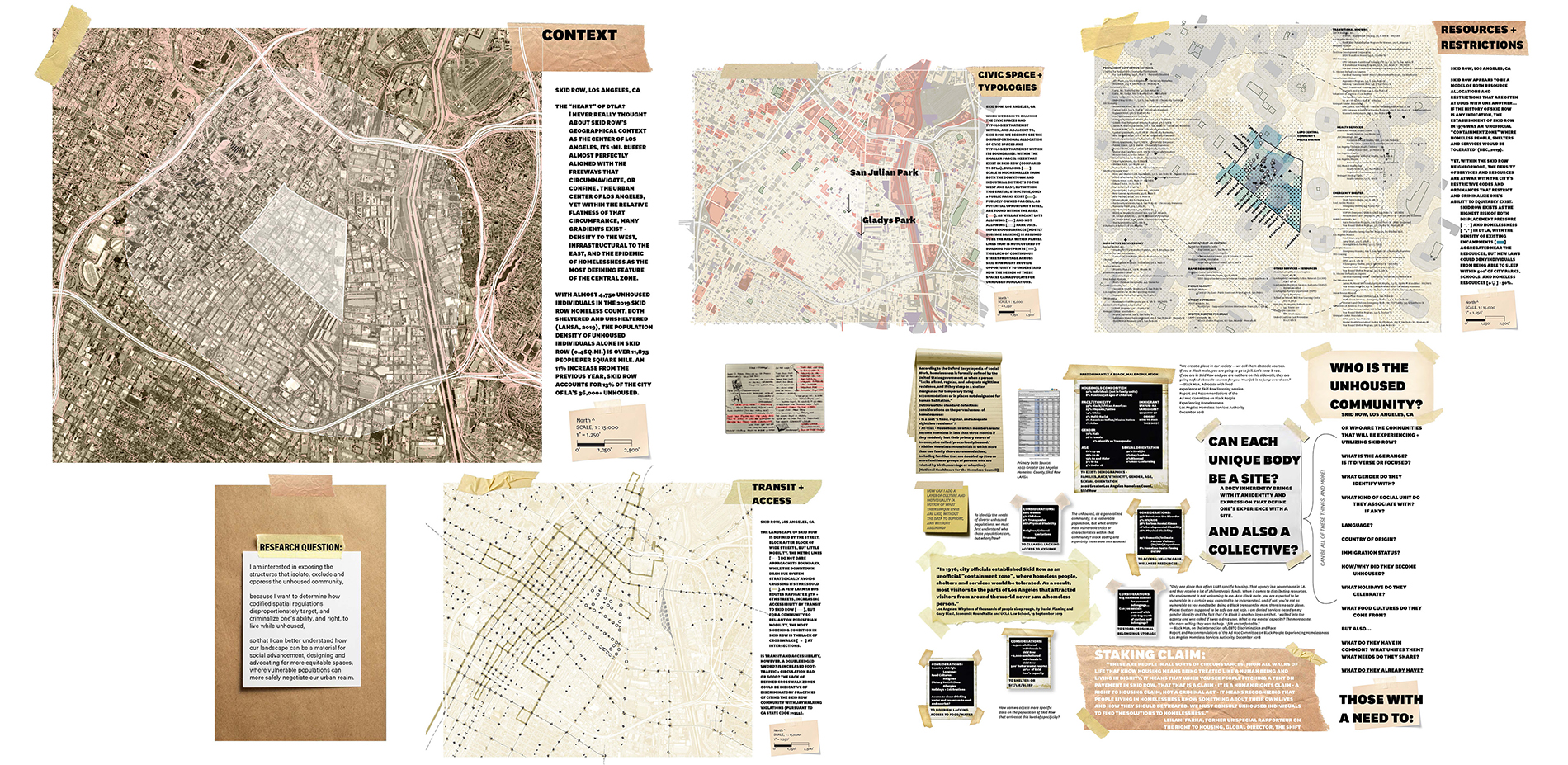

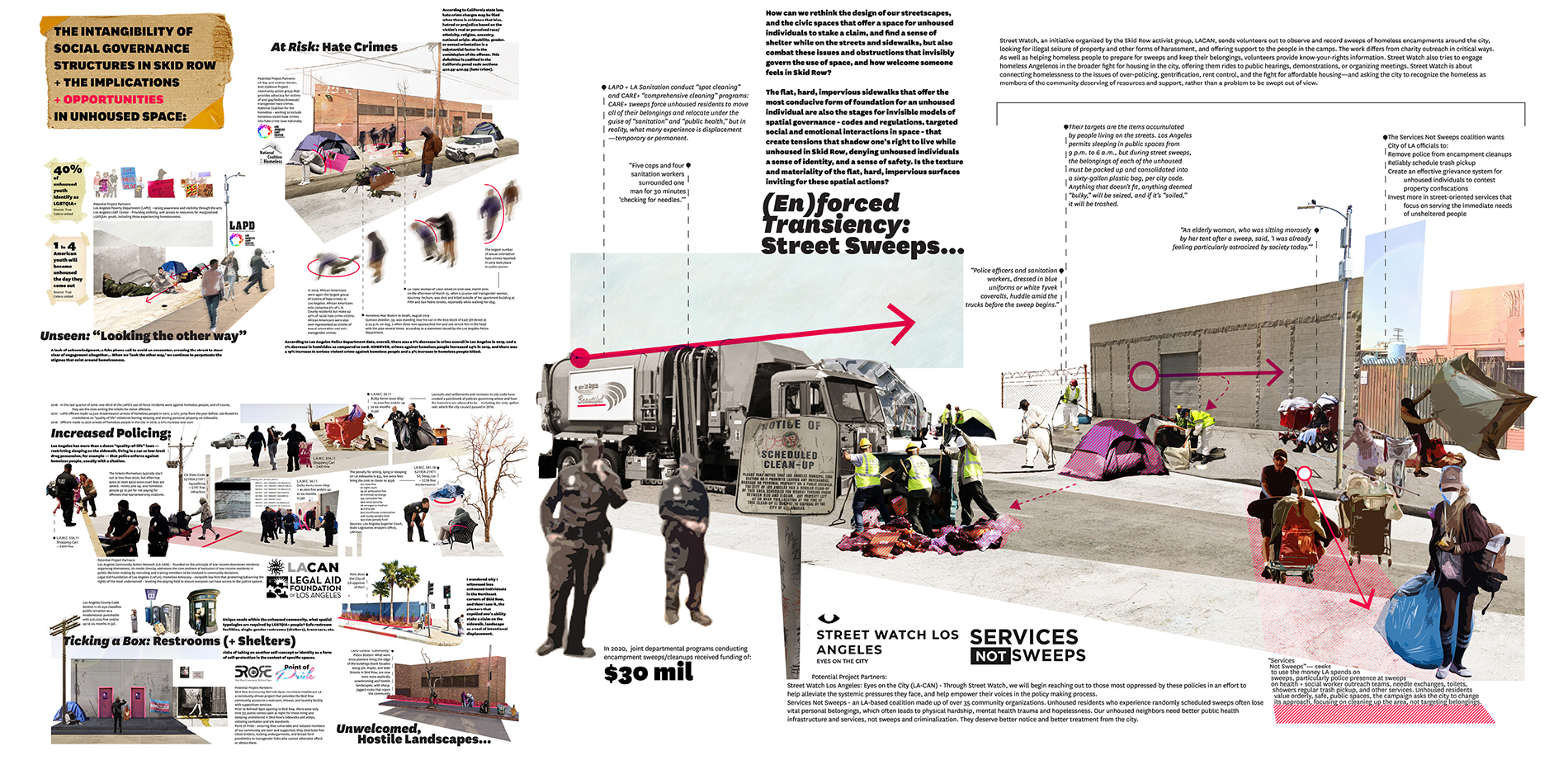

The largest congregate setting of LA County’s 66,000+ unhoused individuals resides in the streets of Skid Row, an ‘unofficial containment zone’ for homelessness. For as long as it takes to deliver a housing solution, unhoused communities will continue to suffer at the hands of our codified systems of regulations, like the LA Municipal Code (LAMC). Enduring discrimination for their very existence, unhoused individuals must navigate the LAPD’s yearly 14,000+ misdemeanor arrests attributed to ‘quality of life’ violations that prohibit sitting, lying, or sleeping on sidewalks (LAMC§41.18), but to identify as LGBTQIA+ and unhoused means to be doubly discriminated against. LGBTQIA+ individuals (and the 40% of unhoused youths who identify as LGBTQIA+) are further oppressed by hate crimes, threats of physical violence, and tensions that encourage many to conceal their own identities in order to access resources, and survive. This research spatializes the LAMC, designing a survival guide for the unhoused to more safely negotiate our civic spaces, and stake a more dignified claim in a landscape that so strictly governs their ability to even exist.

Project Narrative

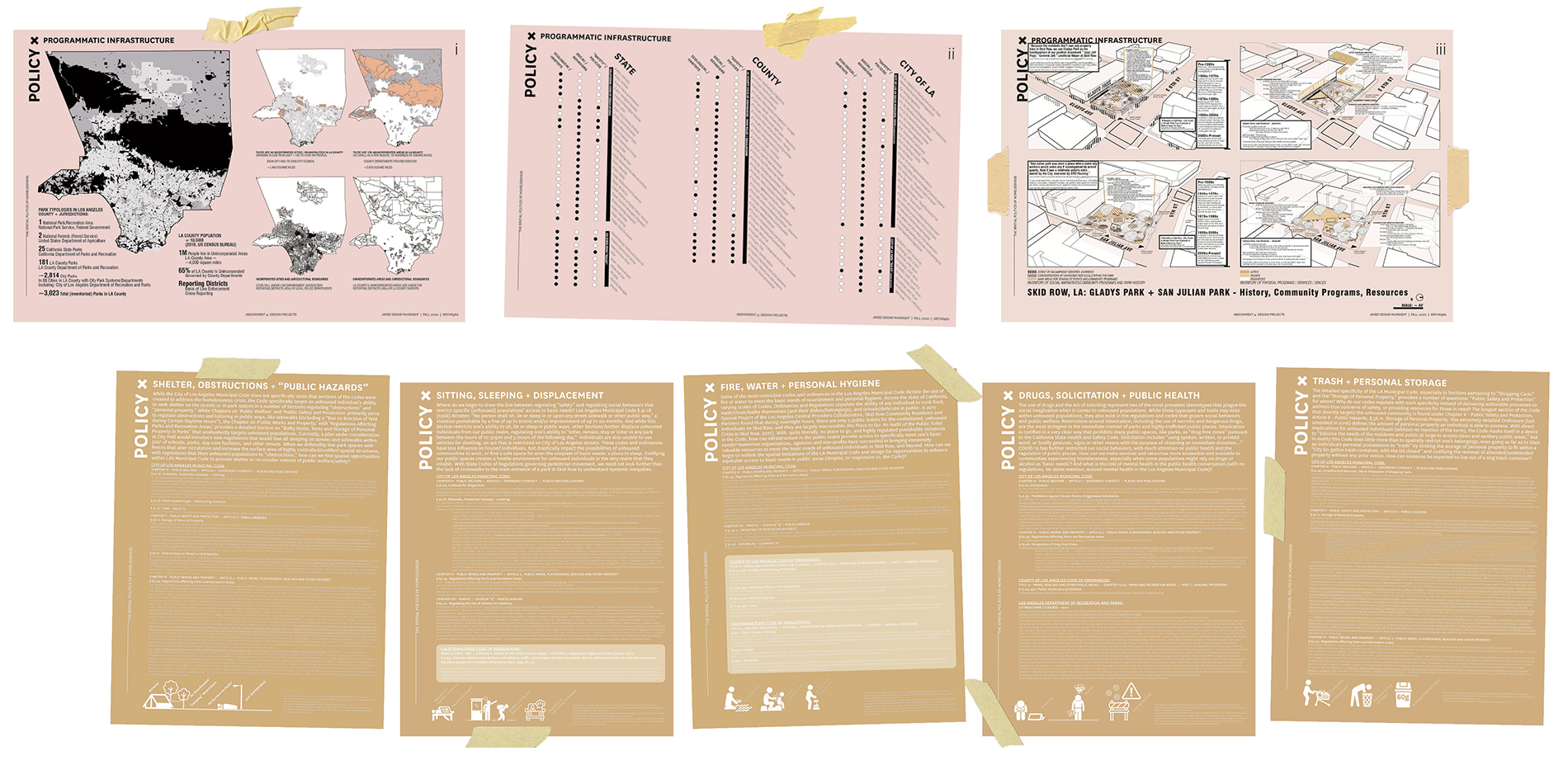

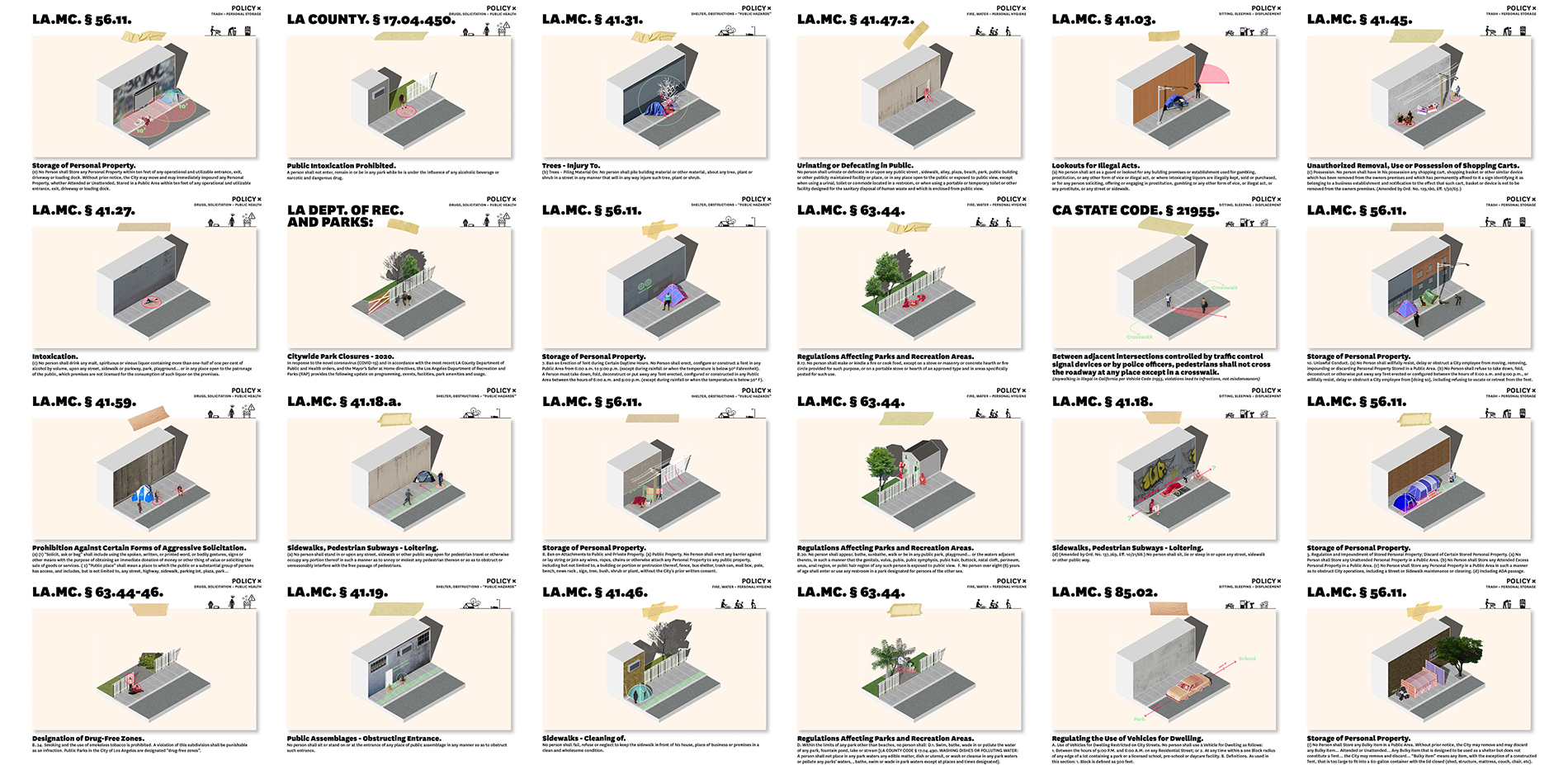

This research explores the explicit and implicit nature of policy in design, looking at the systems of rules, codes, and ordinances, that govern human behaviors in our civic spaces in Los Angeles. Through a deep investigation into the Los Angeles Municipal Code, and the complexity of regulations found across numerous chapters, articles and sections of the code, that target individuals for the simple fact that they might not have another option for shelter, I began re-organizing the categories of regulations to better understand their spatial implications, finding that almost every instance of one’s daily life and routine is punishable while unhoused.

This research is focused in Skid Row, exploring the democratization of our civic spaces to propose alternate ways that the landscape can be a material for social advancement. The largest congregate setting of LA County’s 66,000+ unhoused individuals resides in the streets of Skid Row, and for as long as it takes to deliver a housing solution, our unhoused communities will continue to suffer at the hands of our codified systems of regulations, like the LA Municipal Code, that restrict and criminalize their abilities to even exist in space.

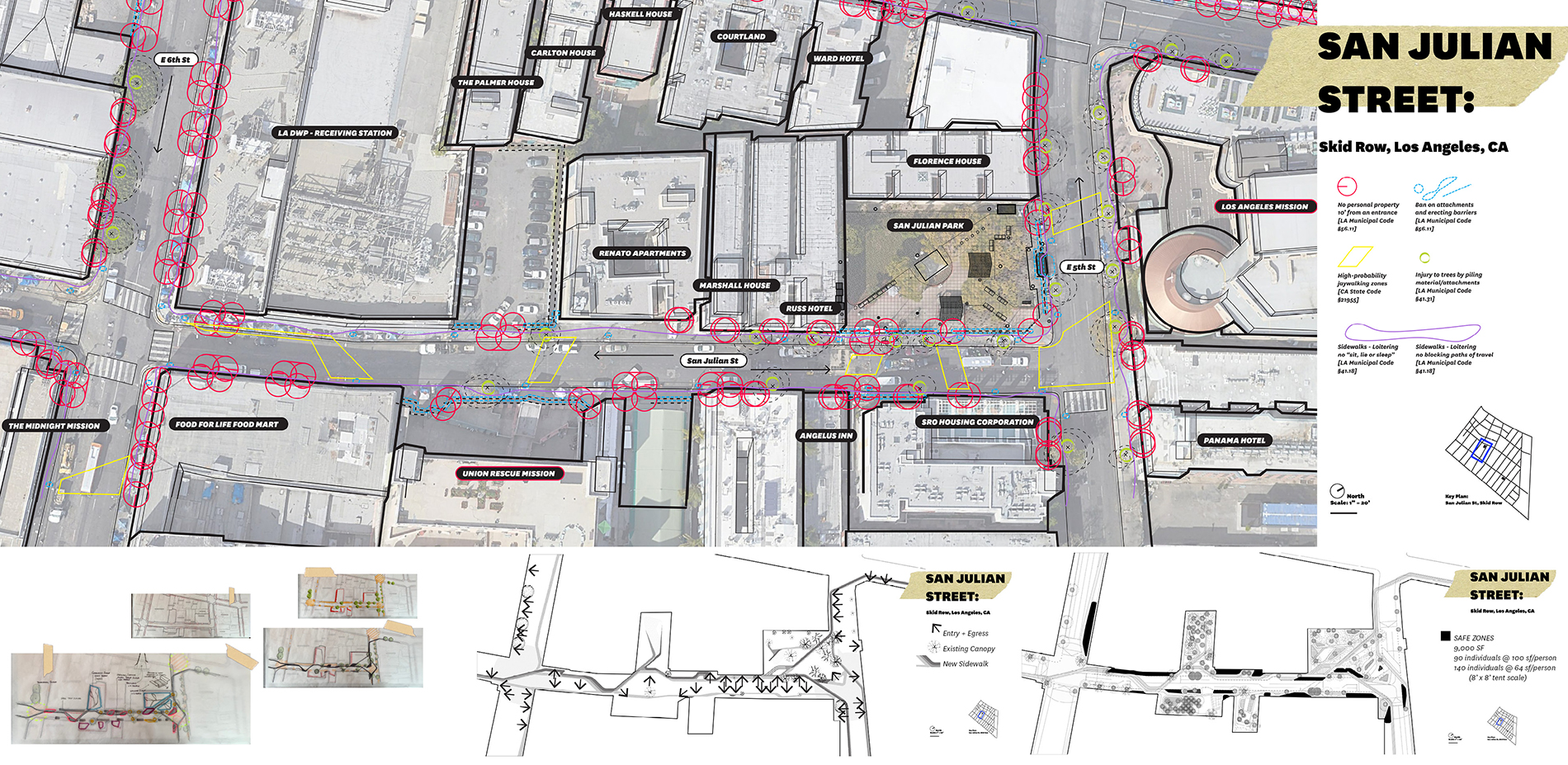

Skid Row has only 2 parks in its 51-block area, and over 28 intersections without crosswalks (I speculate as a means for more jaywalking citations). Since the 1970s, Skid Row has been an “unofficial containment zone” for homelessness, offering hundreds of resources, to attract unhoused individuals away from tourist destinations.

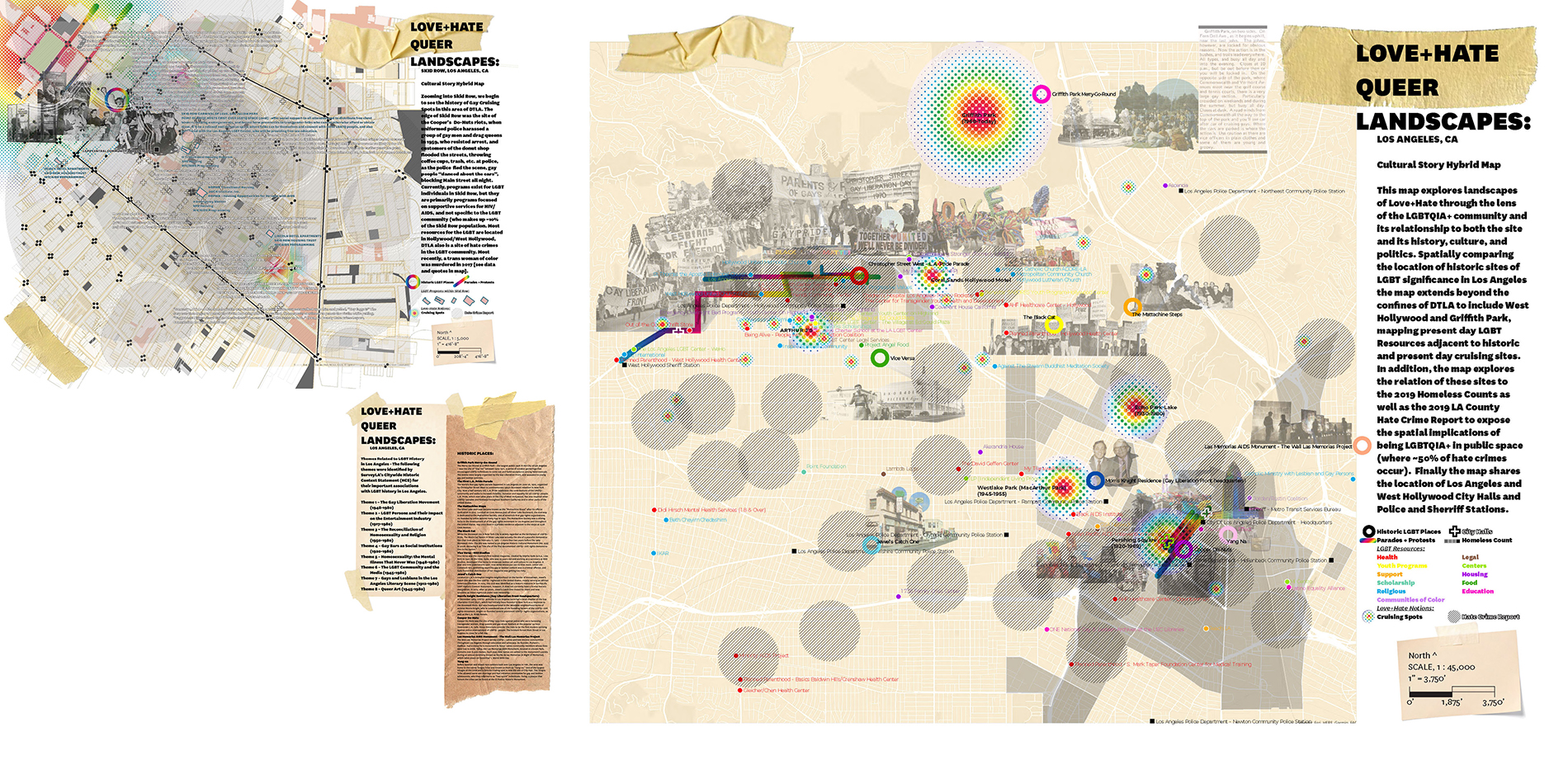

Enduring discrimination for their very existence, unhoused individuals must navigate the LAPD’s yearly 14,000+ misdemeanor arrests attributed to “quality of life” violations that prohibit sitting, lying or sleeping on sidewalks (LAMC§41.18), but to identify as LGBTQ and unhoused means to be DOUBLY discriminated against. LGBTQ individuals (and the 40% of unhoused youths who identify as LGBTQ) are further oppressed by hate crimes, threats of physical violence, and tensions that encourage many to conceal their own identities in order to access resources, and to survive. Though over 12% of the Skid Row community identifies as LGBTQIA+, there exist no specific resources for LGBTQ individuals in the constrained resourcefulness that is Skid Row.

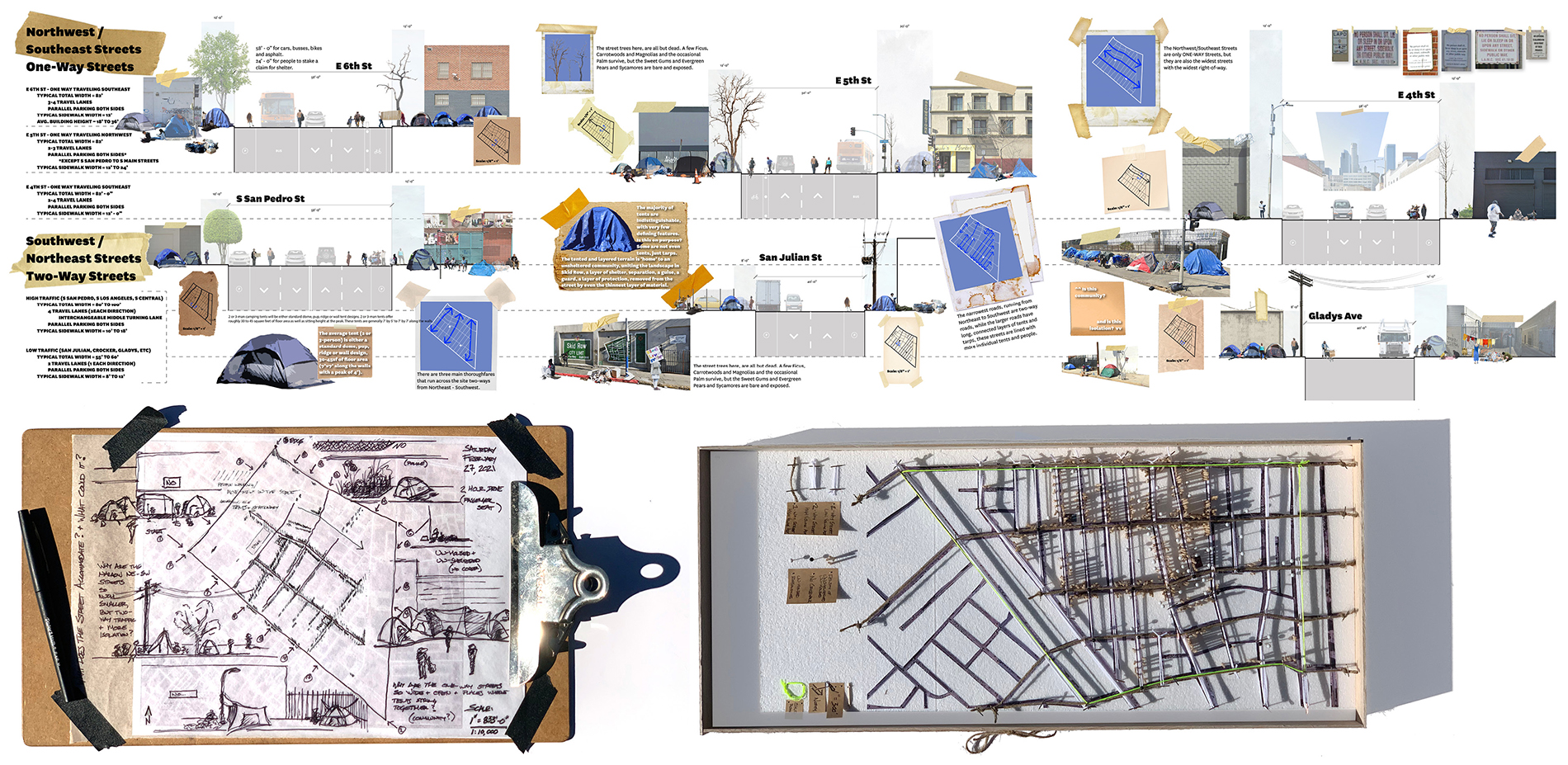

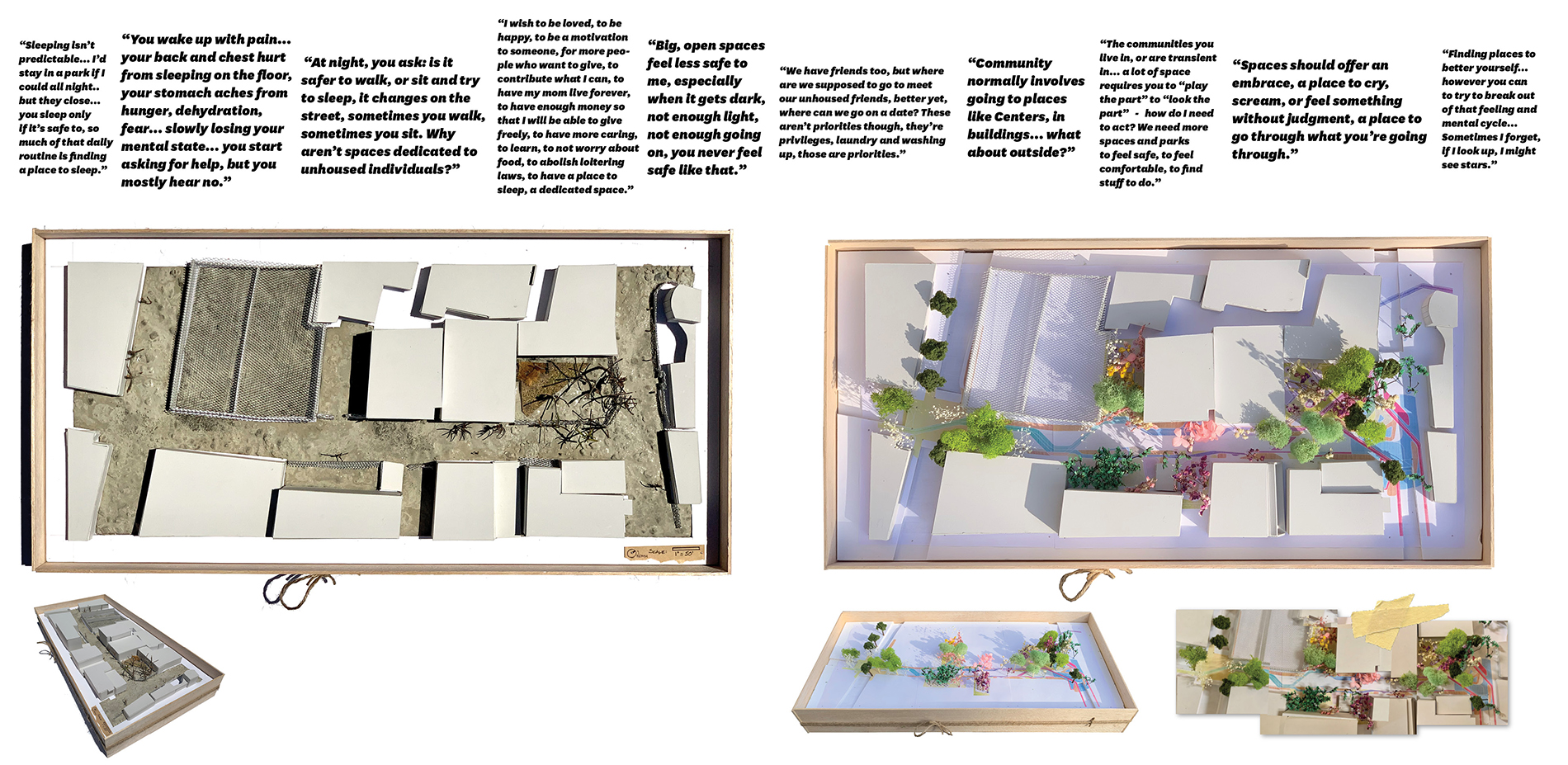

The research began in reading, mapping, and on-site documentation, spending significant time in Skid Row to non-intrusively explore the unique conditions of the site through site visits, drawings, sketching, writing, and modeling.

My interest in the codified landscape stems from a desire to expose other intangible and unseen conditions that govern one’s ability to have a dignified existence on the street: the effect that “looking the other way” has on the unhoused individual’s psyche; the physicality of hate crimes that shadow and threaten life on the streets; the increased policing, citations and incarcerations; lack of access to public restrooms; hostile landscapes, that criminalize one’s existence; and the enforced transiency that occurs in the process of a Street Sweep, when unhoused individuals are forced to “move along” with only what they can carry in a 60g container (LAMC§56.11).

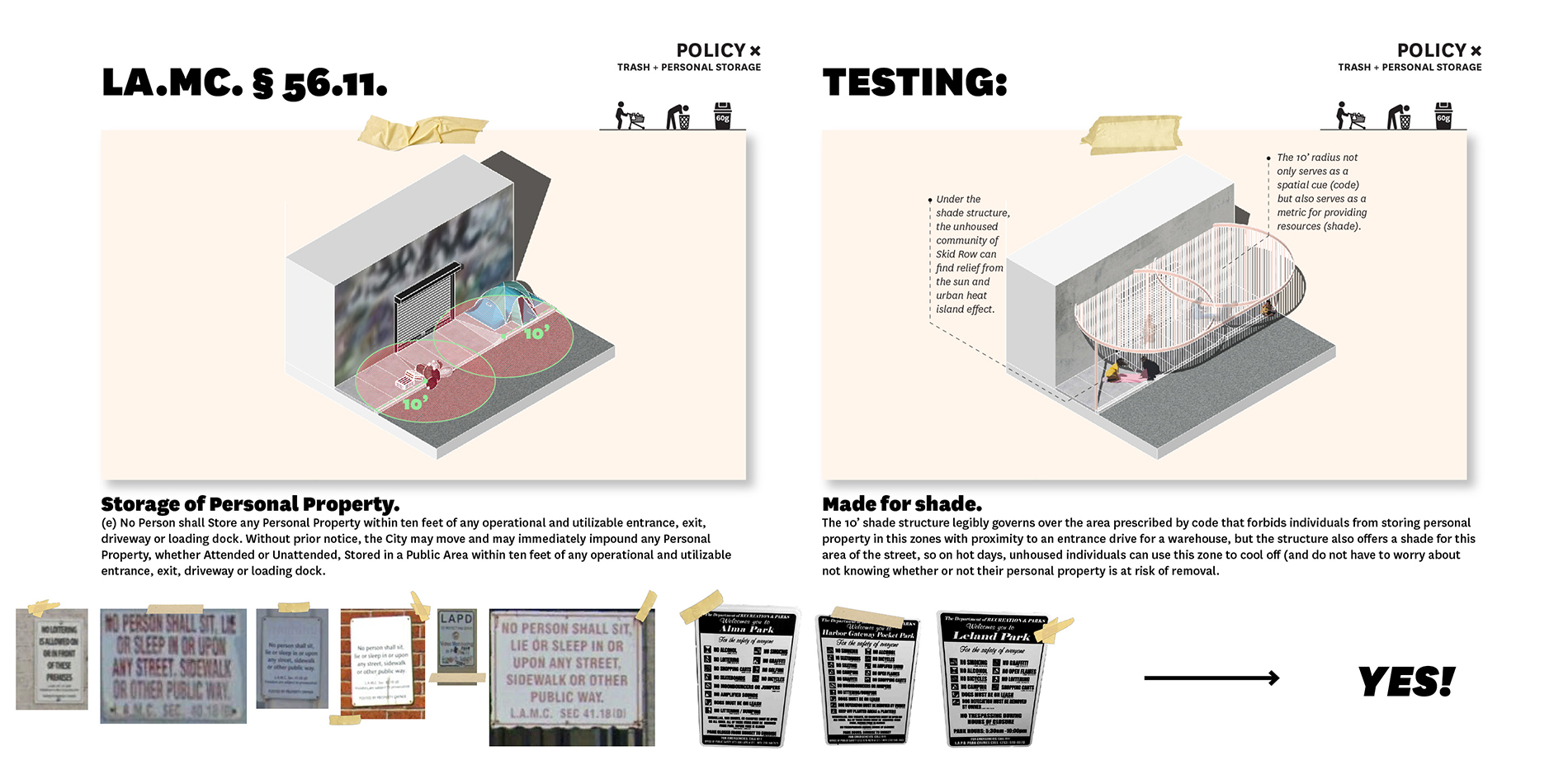

I am working to spatialize the LA Municipal Code to help the unhoused legibly understand how they can legally exist in public space, to identify opportunities that challenge the structures that isolate, exclude and target the vulnerabilities of a community without other options.

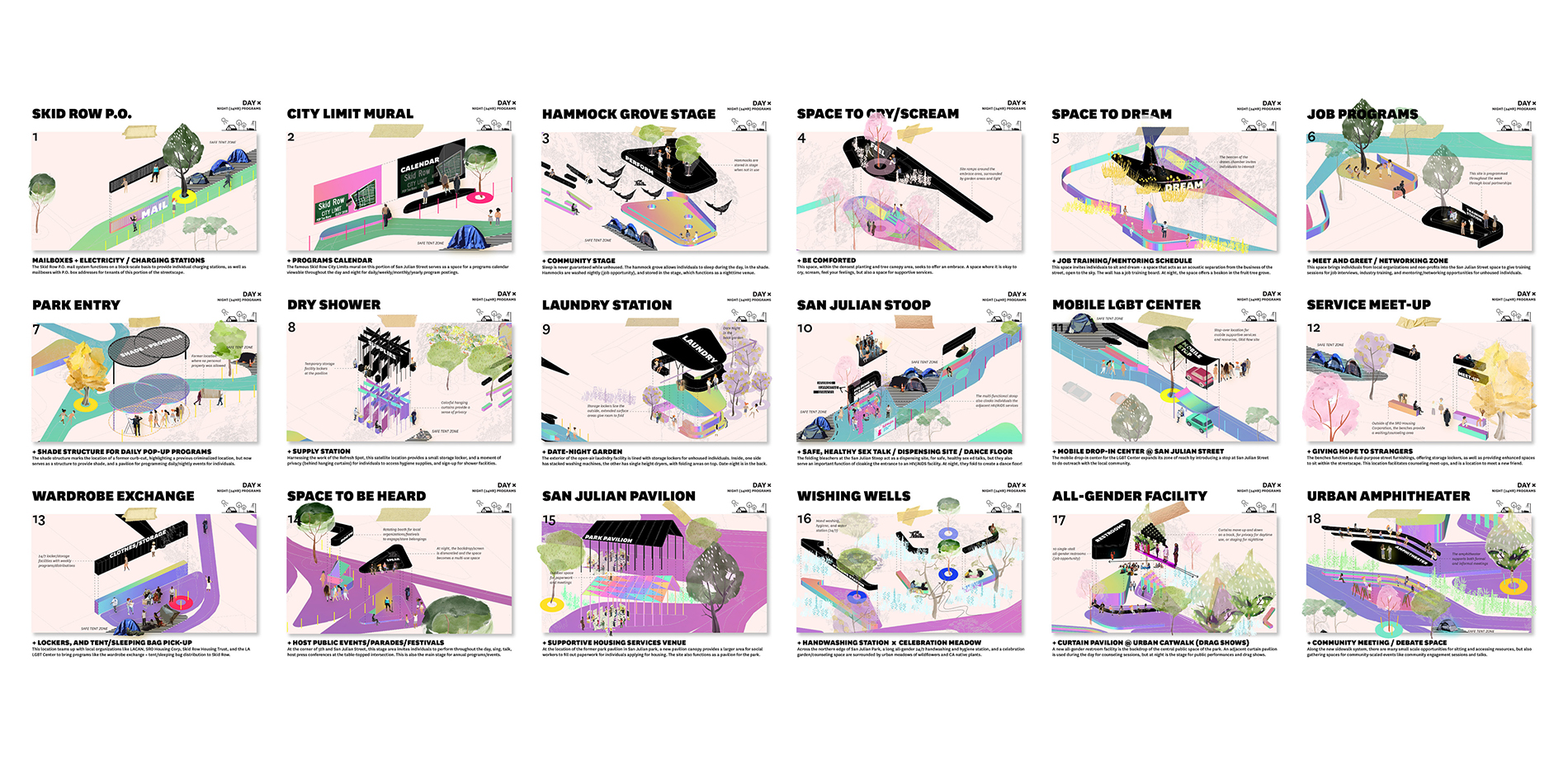

LAMC§56.11 prohibits the storage of personal belongings within 10’ of an operable entrance. My inquiries redirect that codified statement in the design a multi-purpose shade structure enveloping that 10’ radius to: clearly define where personal property is at risk of confiscation, provide a refuge for programmed and supportive services, and a respite from excessive heat and Los Angeles’ rising temperatures. A design that serves as a survival guide for the unhoused to more safely negotiate civic spaces as inclusive environments.

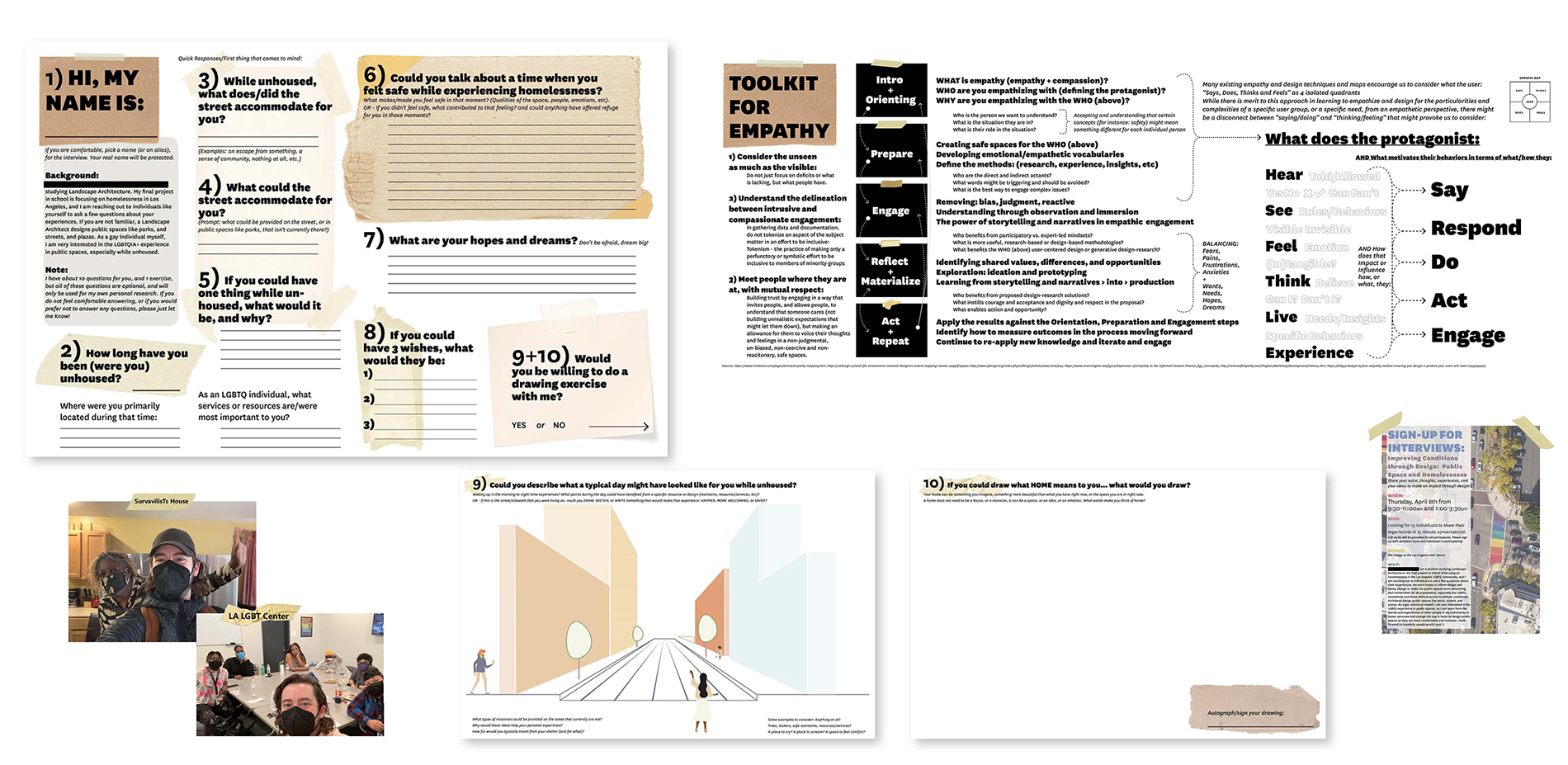

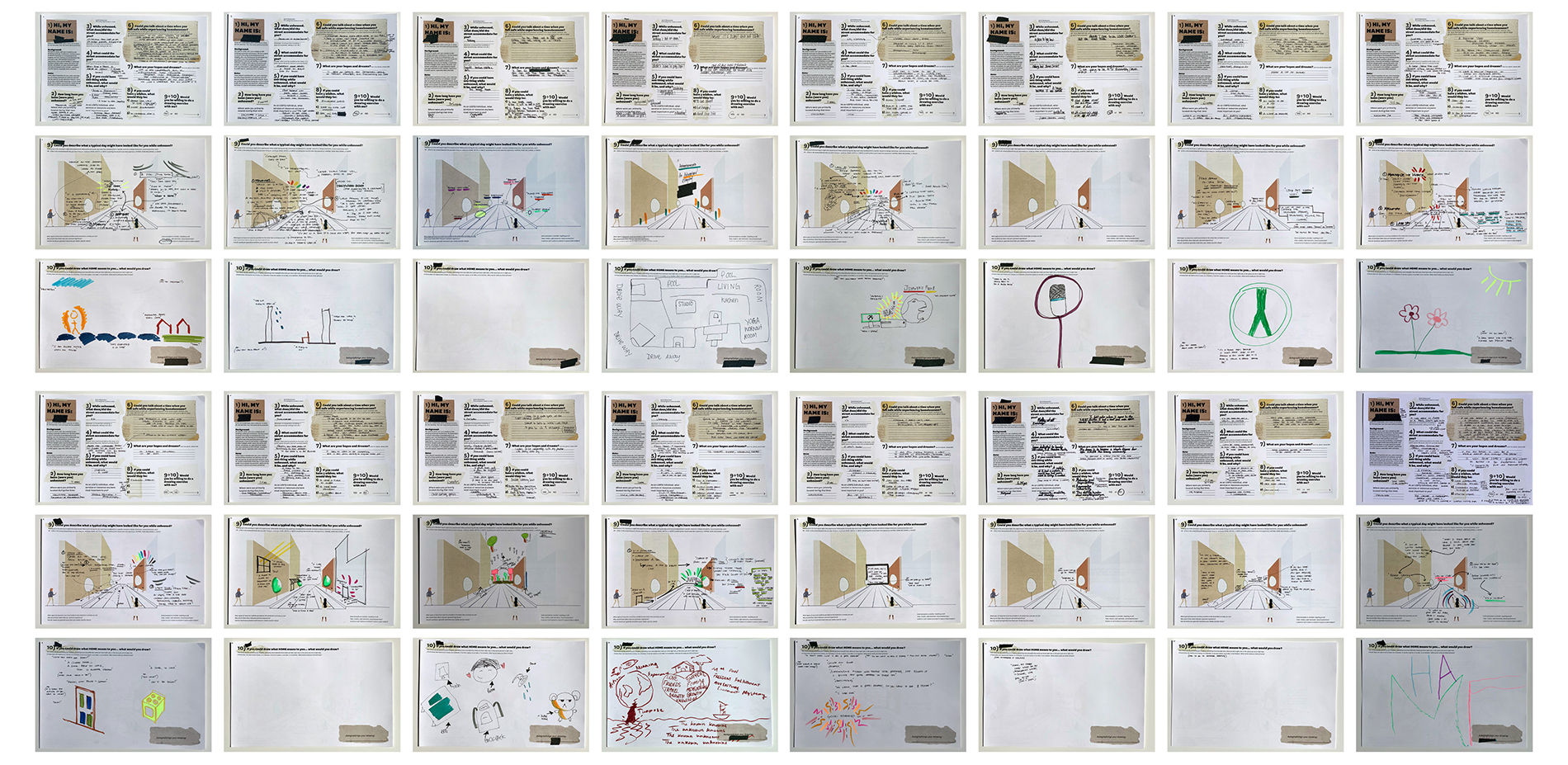

Fostering a deeper sense of empathy for those least represented, and those whose voices, and identities, are not often heard or designed for, is at the core of my design process. In addition to my research, and site visits, I have conducted over 30 interviews with individuals like Ms. Phyllis, and Jo and the team at the LA LGBT Center, where in April 2021 I conducted community engagement sessions with young adults experiencing homelessness.

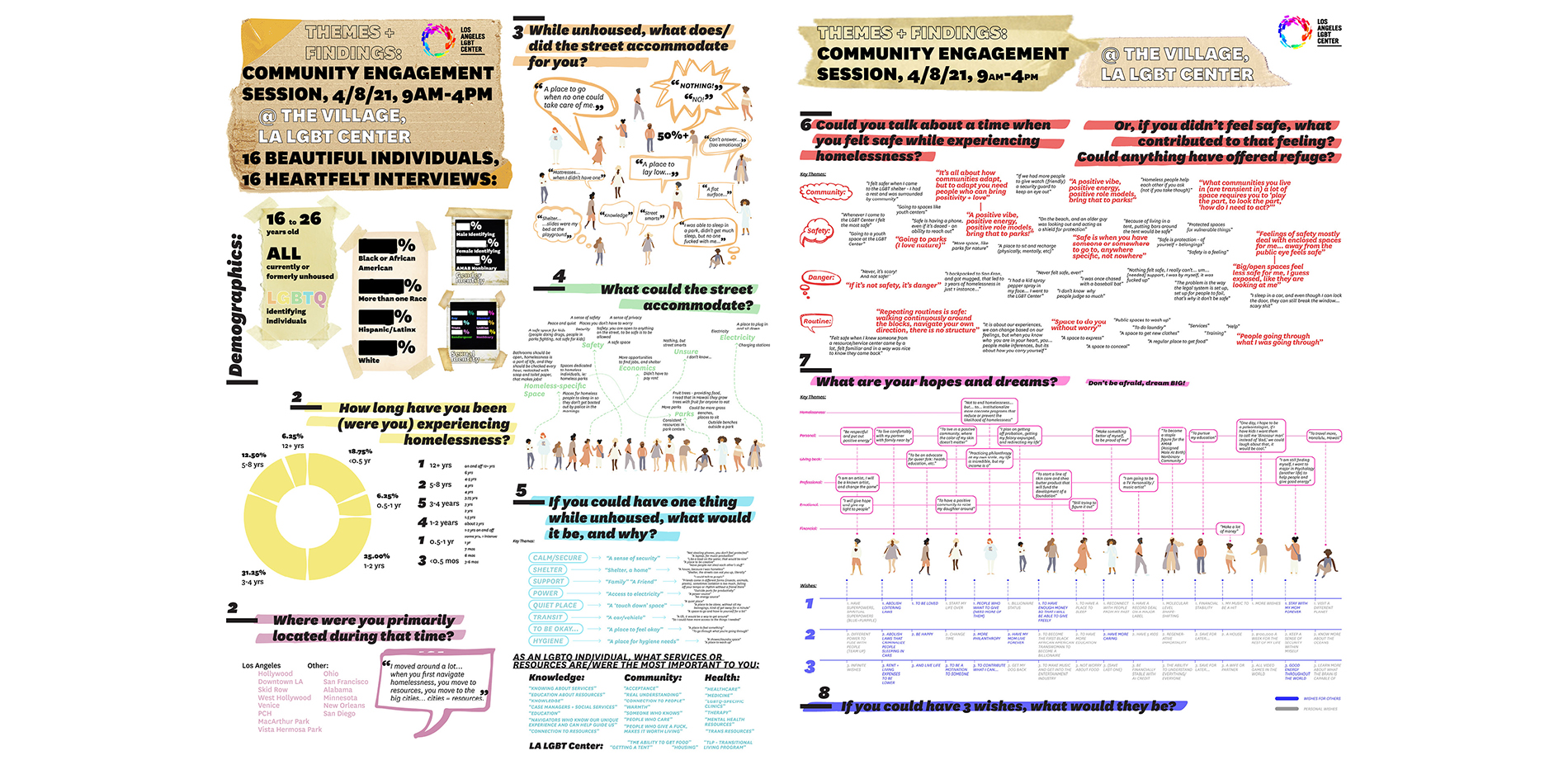

Designing my own materials to engage in listening sessions, I wanted to not only understand their experiences, but also inspire them to dream with me. This overwhelmingly emotional process allowed me to have 16 one-on-one conversations with unhoused LGBTQ individuals, who invited me into a day in their lives to learn from their experiences. These 16 heartfelt interviews revealed a combined 50+ years of lived unhoused experiences, with notions into what the street does and could accommodate, information into the most important resources while they were experiencing homelessness, and what contributes to feelings of safety, and danger, at an extremely intimate scale.

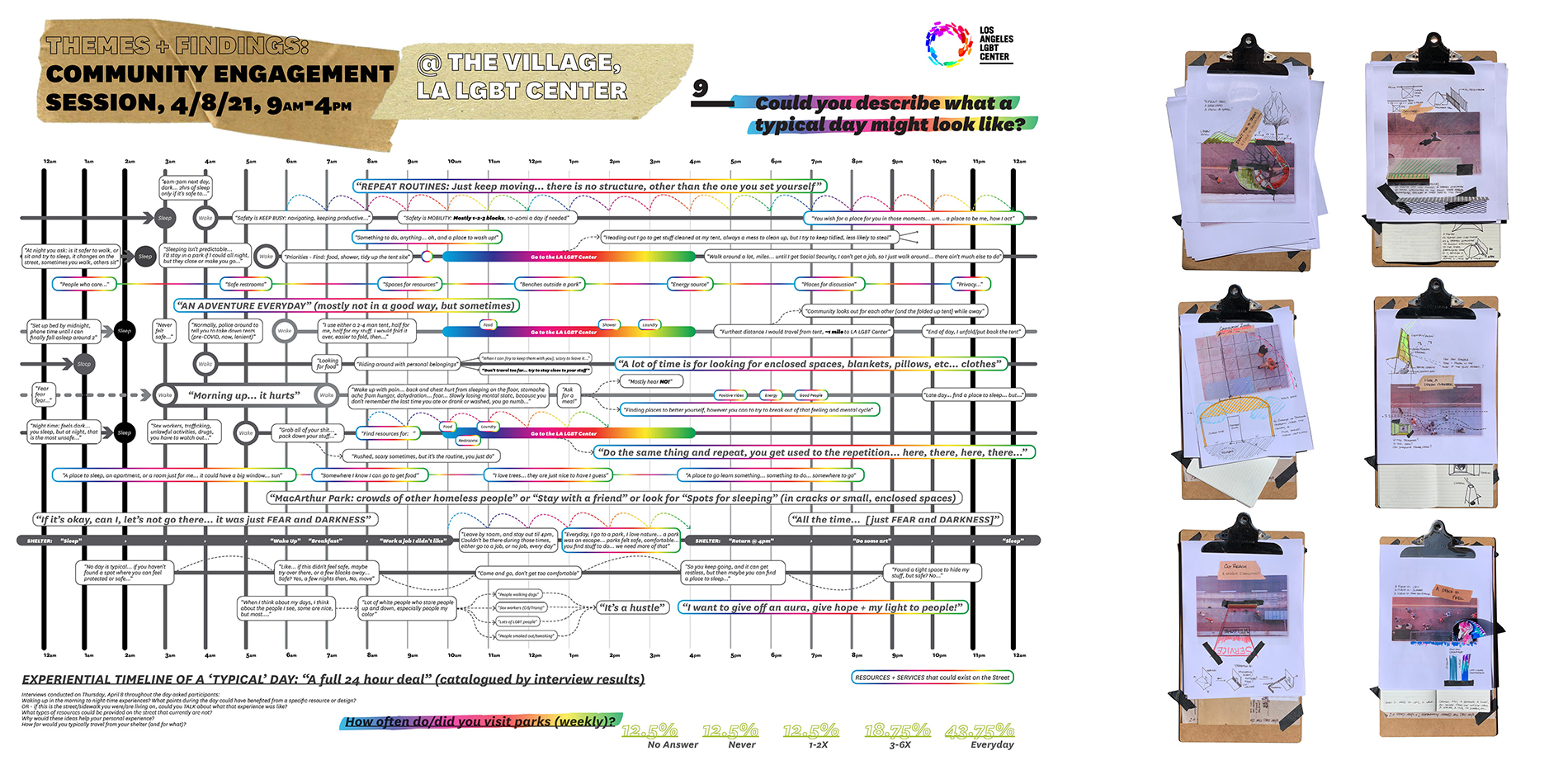

But the work also revealed their hopes and wishes that extended beyond themselves, with a true desire to give back in meaningful ways to ensure others would not have to endure those same experiences, on the cold, hard, and painful concrete that is the foundation of much of their existence while unhoused. This engaged research revealed that no day is typical. The unhoused experience, in the landscapes that we design, is a full 24-hour deal, where sleep is never guaranteed, and the length of the day is determined by one’s ability to develop and repeat routines.

So much of that daily experience tells people what they can’t do, but what if our landscapes began asserting what you can? What if our landscapes learned from these narratives, and invited us to hope? What does it mean to design a landscape where someone can cry or scream without judgment? How can we welcome emotions at a human scale through ideas that lessen the stress and trauma that already exists in these spaces, and give someone an opportunity to do the things they might not think they can – pavilions to recharge your humanity.

There is no such thing as an urban void for the unhoused. These all-too-often continuous, impervious spaces of the city are the places they inhabit and navigate. To be unhoused means to be exposed, sticking out against the mundane, grey, and fenced backdrops of the sidewalk. A sidewalk, by definition, is the portion of a street between a curb line and property line, but by code, a sidewalk is an unlawful home. What if the sidewalk was no longer limited to the cattle-chute-like conditions that criminalize the unhoused existence?

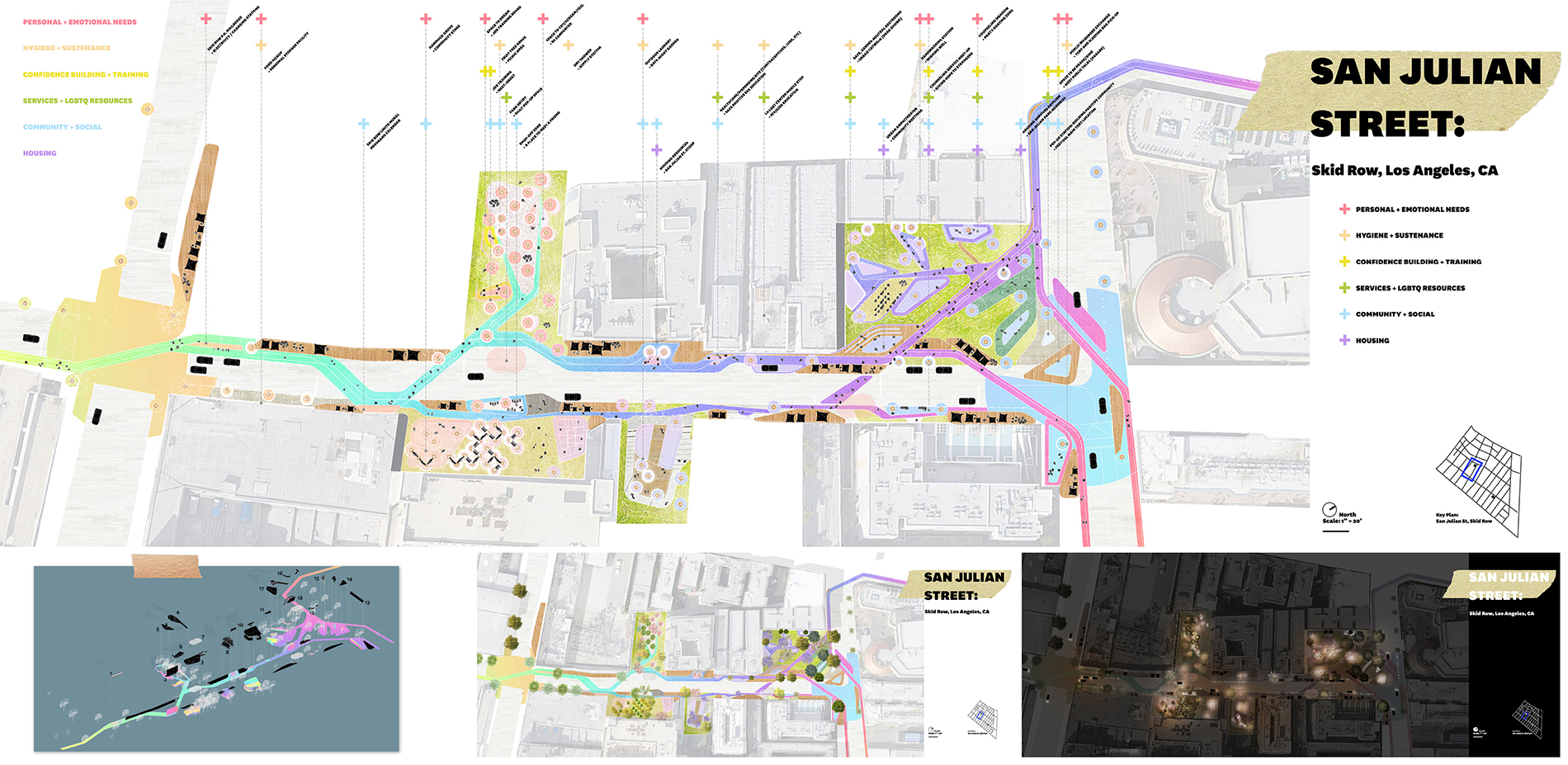

What if we radically re-imagined a new methodology for the sidewalk, redirecting this codified urban circulation system to acknowledge criminalization, re-routing the sidewalk through the lens of the code, in a design that legibly asserts a new circulation system in Skid Row, for the unhoused, extending supportive services and resources in a new streetscape typology. The true innovation of this methodology is that in redefining our own registration of the sidewalk, we redirect the code’s restrictiveness, resulting in the creation of new safe spaces that evolve throughout the 24-hour experience that it is to be unhoused, and allow individuals to safely sit, lie, sleep, and store their personal belongings.

It is no wonder so many unhoused individuals prefer to conceal their own identities, and forms of self-expression, in a context where they are criminalized for their very existence. Through the integration of unhoused individuals into an uncriminalizing landscape, designed to give that experience a voice, maybe we can not only redirect the sidewalk, but also our discriminatory policies. This research and work is a call to attention, and a call to action.

To be unhoused is not to be sedentary in a tent, it is to be in a constant state of motion, and emotion, our landscape’s should acknowledge that, and allow unhoused individuals to stake a more dignified claim in a landscape that so strictly governs their ability to even exist.

Plant List:

- Albizia julibrissin, Silk Tree

- Bauhinia variegata 'Candida', White Orchid Tree

- Calocedrus decurrens, Incense Cedar

- Cercis occidentalis, Western Redbud

- Chilopsis linearis, Desert Willow

- Citrus limon, Lemon Tree

- Citrus sinensis, Orange Tree

- Ficus rubiginosa, Rusty Leaf Fig

- Jacaranda mimosifolia, Jacaranda

- Juglans californica, Southern California Black Walnut

- Lagerstroemia indica, Crape Myrtle

- Lyonothamnus floribundus, Catalina Ironwood

- Melaleuca viminalis, Weeping Bottle Brush

- Parkinsonia microphylla, Yellow Palo Verde

- Pinus torreyana, Torrey Pine

- Pistacia chinensis, Chinese Pistache

- Platanus racemosa, Western Sycamore

- Populus fremontii, Fremont Cottonwood

- Prunus andersonii, Desert Peach

- Prunus emarginata, Bitter Cherry

- Prunus ilicifolia, Hollyleaf Cherry

- Psorothamnus spinosus, Smoke Tree

- Quercus agrifolia, Coast Live Oak

- Salix laevigata, Red Willow