Honor Award

Access to Nature for Older Adults: Promoting Health Through Landscape Design

Multi-Regional USA

Center for Health Systems & Design, Texas A&M University, USA

Close Me!

Close Me!People and Places. This project compared the quality of landscape features at assisted living facilities, with actual levels of outdoor usage by residents. The purpose was to determine whether residents spent more time outdoor at facilities where the outdoor areas received better ratings.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 1 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Climate and Cities. The effect of climate on outdoor usage was explored by conducting the study in three diverse climate regions, each centered on one of the 10 main megapolitan areas emerging in the U.S.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 2 of 15

Close Me!

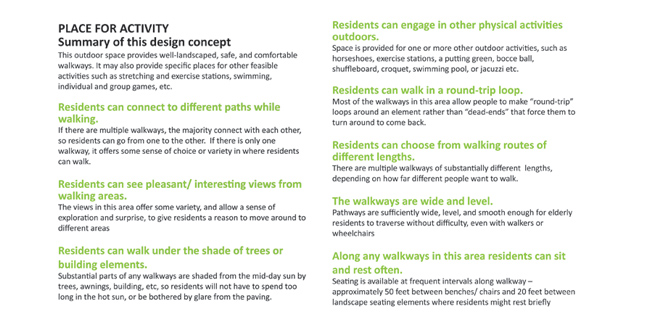

Close Me!Core Design Concepts. Core design concepts were developed from previous research and design recommendations, yielding the following domains: 1) Nature elements; 2) Choice / autonomy; 3) Safety / security; 4) Comfort / accessibility; 5) Activity. Landscape architects can optimize these principles in their design solutions.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 3 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Evaluating Landscape Features. Researchers rated the usability of approximately 90 different aspects of each of the outdoor spaces, using a newly developed evaluation tool and objective measurements.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 4 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Evaluation Tool. This example shows part of the evaluation tool used to rate outdoor spaces. Each item was rated on a scale from 1-10, based on how well this aspect of the landscape would support usage by an older adult.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 5 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Survey & Interview Process. Researchers visited 68 assisted living facilities in three different climate regions, collecting information from 1,560 residents and staff about the role of the outdoor landscape in their lives.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 6 of 15

Close Me!

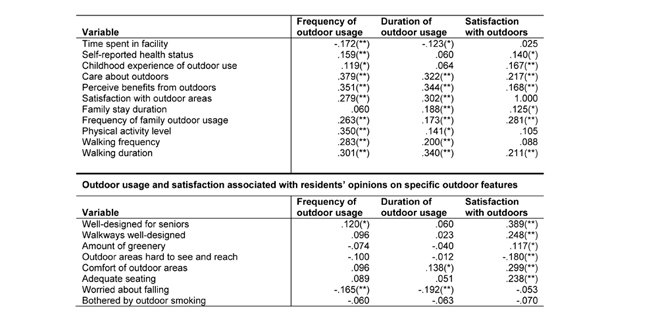

Close Me!Outdoor Usage Related to Other Variables. Several nonenvironmental factors were related to residents’ levels of outdoor usage and satisfaction. These included their background, level of walking and physical activity, and their opinions about the outdoor areas at their facility.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 7 of 15

Close Me!

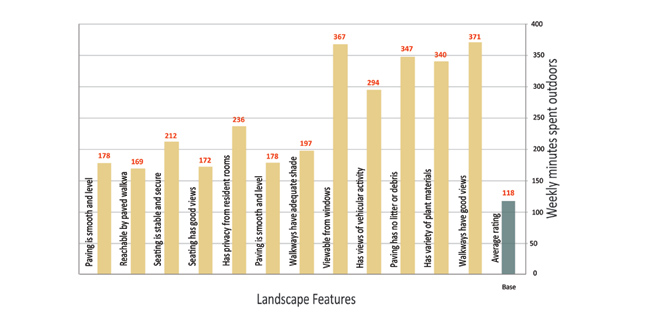

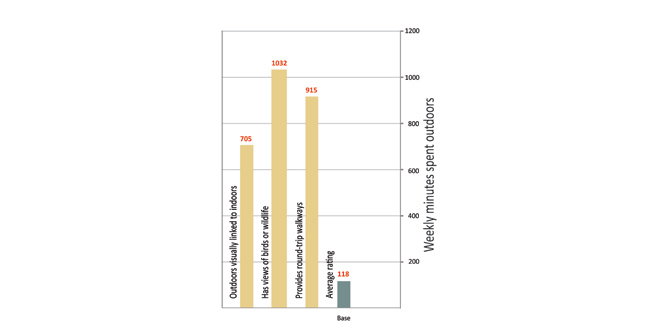

Close Me!Landscape Features that Increased Outdoor Usage. This portion of the bar graph shows features that increased time spent outdoors up to approximately 3.5 times the baseline at facilities where this feature was rated as average.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 8 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Landscape Features that Increased Outdoor Usage. The baseline of 118 shows outdoor usage when all features were rated at 5 out of 10 possible points. The bars show increased outdoor usage where specific features were rated at 8 instead of 5, with everything else held constant.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 9 of 15

Close Me!

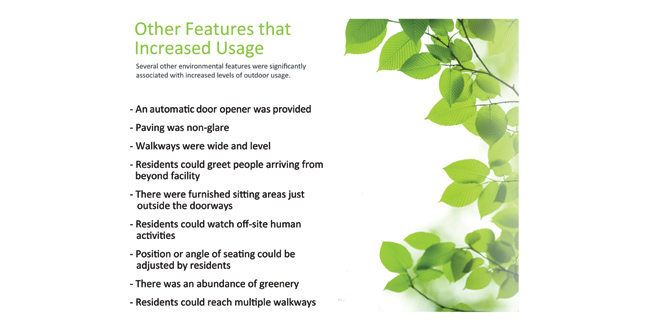

Close Me!Other Features that Increase Usage. Several other environmental features were significantly associated with increased levels of outdoor usage.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 10 of 15

Close Me!

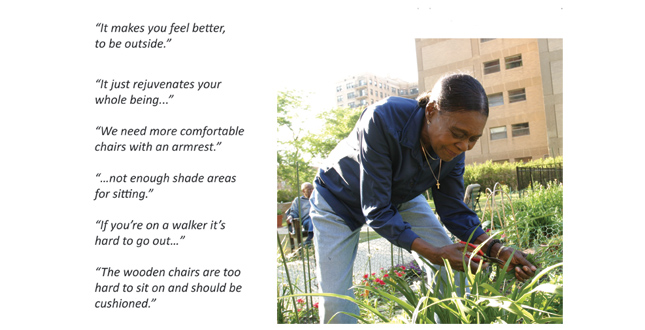

Close Me!What Residents had to say… Most residents indicated they enjoyed being able to spend time outdoors, but many had concerns regarding the design and furnishing of existing landscaped spaces at their facility.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 11 of 15

Close Me!

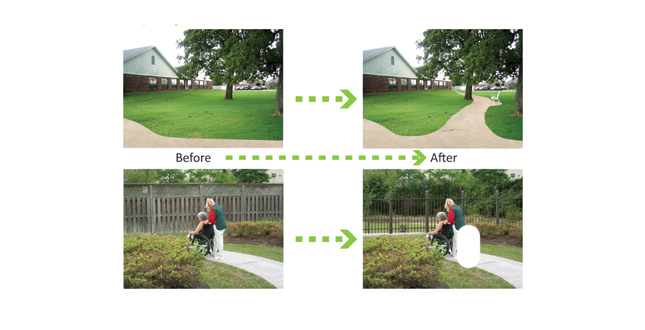

Close Me!Small Changes Big Impacts. This example show how the key design concepts can be applied in a typical long-term care outdoor environment. Adding a new walkway and opening up an existing fence allows residents to see and reach more of the landscape.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 12 of 15

Close Me!

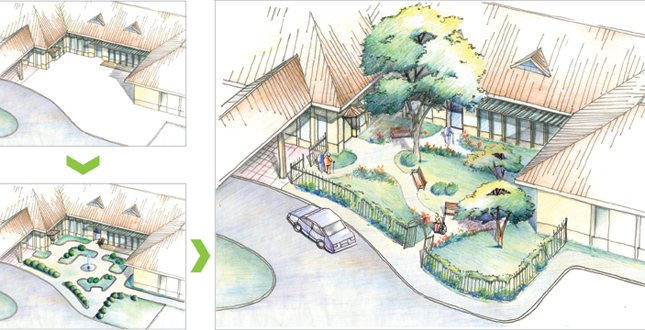

Close Me!Applying Research: Entry Garden. A landscaped entry garden near the main lobby is a research-based design element that promotes social interaction, encourages increased outdoor usage, and provides a sense of connection with the world beyond the facility walls.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 13 of 15

Close Me!

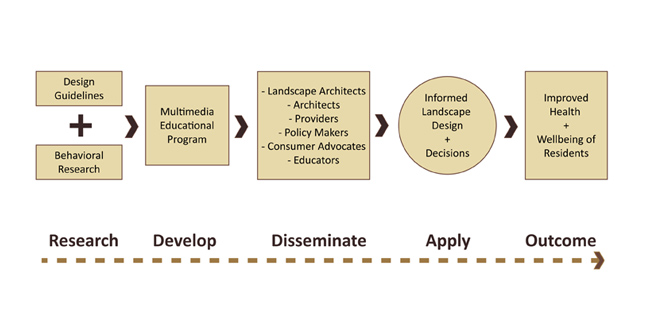

Close Me!Research Dissemination. This flowchart shows how research can be disseminated to diverse stakeholders in long-term care, with subsequent informed decision making leading to supportive landscape design and improved health outcomes.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 14 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Educational Program. To make it easier for multiple stakeholders to translate research to practical design decisions, a multifaceted educational program incorporates case studies, diagrams, sketches, and 3-D animations in a series of educational videos, accompanied by online resources such as interactive exercises.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Susan Rodiek

Photo 15 of 15

Project Statement

This study assessed how landscape design influenced outdoor usage at assisted living facilities. After evaluating 68 randomly selected facilities in diverse climates, and surveying 1,560 residents and staff, several landscape features were found to be strongly associated with outdoor usage. Because contact with nature is known to have significant health benefits, well-informed landscape architects may contribute to public health by improving the well-being of frail elderly residents in long-term care settings.

Project Narrative

—2010 Professional Awards Jury

Having access to nature and the outdoors has long been considered therapeutic for elderly residents in long-term care settings. Research is beginning to confirm that spending time outdoors may improve sleeping patterns, reduce pain, decrease urinary incontinence and verbal agitation, speed up recovery from disability, and even increase longevity(1-4). Unfortunately, in spite of potential health benefits, outdoor areas at long-term care facilities are often reported as underutilized by elderly residents (5-7). Although several landscape design guidelines have been published, very few outcome-based studies have attempted to measure the effect of landscape features on outdoor usage (8-12). This study addressed the lack of evidence by measuring how the landscape impacted outdoor usage. The findings can help landscape architects design to support the actual needs and preferences of long-term care residents.

Methods

Overview

This study compared the objectively rated qualities of facility outdoor space with the outdoor usage levels of residents, to see if they spent more time outdoors in places with better-rated environments. At 68 randomly selected facilities, landscape features were rated using an evaluation tool based on previous research. Resident and staff survey results (N=1560) were compared with environmental ratings.

Facilities and Climate Regions

This study focused on assisted living, where most residents are still able to access the outdoors independently. Only facilities with 50+ residents were included, because problems with outdoor access were expected to be greater in institutional-size settings. To account for the effect of climate on outdoor usage, research was carried out in three distinct climate zones, chosen from the 10 primary emerging megapolitan regions of the US (13-14). In each area, approximately 20 facilities were randomly selected within a two-hour driving diameter in each region's main city: Houston, Chicago, and Seattle. This resulted in 68 facilities, ranging from dense urban settings to outlying suburbs and towns.

Evaluating the Outdoor Environment

The main design concepts (hypotheses) tested in this study were derived from previous research and "best-practice" guidelines published by experienced landscape architects, architects, gerontologists and care providers1(5-19); these sources generally agreed on the main environmental qualities that influence outdoor access for older adults. A set of core design concepts was extracted from the most commonly cited issues, and developed into a checklist-based evaluation tool. To maintain the reliability of the findings, the same team of trained researchers evaluated all sites, rating about 2+ spaces per facility.

Evaluation Tool

To test the design concepts, researchers evaluated the "usability" of each feature from the resident's perspective. Thus, instead of rating a walkway as a physical object, it was rated according to how easily an elderly resident could navigate that walkway. Each of the core design concepts was evaluated by rating a cluster of environmental features that appeared to be the main elements embodying that concept. Each feature was rated on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being "an extremely poor example," 5 being "average" and 10 being "the best that could be expected in this type of setting." In pre-testing, the evaluation tool was found to have very high agreement between different raters (interrater reliability tests found Cronbach's alpha and intraclass correlation coefficients in the mid 90s; higher than .70 is typically considered adequate reliability). In addition to 63 rated environmental features, several additional environmental elements and qualities were measured directly, such as the presence of an automatic door opener, light levels, or decibels of sound in an outdoor area.

Surveys

Resident surveys were developed to capture outdoor usage and landscape preferences; staff surveys were used to help confirm the resident surveys. After testing several pilot versions, the final surveys each had about 40 questions, with additional write-in responses. Residents (N=1128) completed surveys independently in small group settings, while staff (N=432) completed surveys individually. The average age of residents was about 84 years, with 79 percent women and 21 percent men. The average staff age was about 44, with 89 percent women and 11 percent men. Although staff members were of diverse race and ethnicity, residents were predominantly Caucasian, which is typical of assisted living in the U.S.

Analysis

Methods

Because all residents from a facility shared the same environmental conditions, an analysis method for clustered data was used in STATA (the Huber-White robust covariance estimator). As factor analysis did not lead to significant results, individual audit items were analyzed separately and only those items significant at the level of 0.10 were retained. The final model initially included all possible variables of interest in a linear regression model and used a backwards stepwise approach. At each step, the variable with the highest p-value (the lowest statistical significance) was removed from the model, until the significance levels of all the remaining regression coefficients were 0.10 or lower. While a significance level of 0.10 was used to develop the statistical model, when the analysis was complete, all the environmental features shown in the Results section below were highly significant (at the 0.01 level).

Controls

Aside from questions relating to the main outcomes, a number of personal variables were considered that might influence outdoor usage: gender, age, health, vision, history of falls, mobility, assistance needed with daily activities, urban vs. rural background, and attitudes and preferences about the outdoors. These items were included in the survey, and tested for their significance in the model; those found to be significant were controlled for in the analysis. This allowed each of the rated landscape features to be considered separately, to see how they influenced outdoor usage.

Results

Overview

The study found that the amount of time residents spent outdoors was substantially influenced by several landscape features evaluated by the core design concepts. There was also strong correlation between outdoor usage, levels of walking and physical activity, environmental satisfaction, and the self-reported health of residents.

Main Findings

Overall, this study found that many of the main features that have long been considered important by researchers and design practitioners, such as safe paving, good seating and strong indoor-outdoor connections, are actually measurably related to the outdoor usage of elderly residents, when all other factors are controlled for. The large number of residents used in this study provided enough statistical power to isolate each environmental feature and determine its relationship to resident behavior. In addition to being highly significant, the magnitude of many of these effects is quite large, when shown in a controlled statistical projection. Images 8-9 show the landscape features found to have the strongest correlation with behavior; these are grouped by magnitude of effect. The features shown in Image 8 were found to increase outdoor usage up to 3.5 times; and the features in Figure 9 had an even stronger impact on outdoor usage. Several other features also increased outdoor usage to a lesser extent.

Discussion

Importance of Findings

Collectively, these findings show that the quality of the outdoor environment is strongly linked to important health-related measures and behaviors. For example, Image 8 shows that the feature with lowest impact ('the outdoors can be reached entirely by paved walkways') still increases the amount of time spent outdoors substantially—by an additional 51 minutes per week. Anyone working with older adults in residential care settings knows how hard it is to influence habits such as outdoor usage or physical activity, and this would be a substantial improvement. Image 9 shows that the environmental feature with the highest impact ('the outdoor area has good views of birds and wildlife') is associated with a nearly 10-fold increase in outdoor usage - from 118 minutes per week to 1,032 minutes per week. This is the equivalent of going from about 27 minutes per day to nearly two and a half hours per day, which would be a radical change. As a statistical projection with all other variables held constant, this model does not reflect what would necessarily happen in actual experience, with multiple variables operating in each case. Nonetheless, these results suggest that the qualities of the landscape are likely to have a significant and powerful impact on outdoor usage in long-term care settings. Although some features considered important were not found to be significant, this may possibly be due to correlations among similar features that canceled each other out in the statistical model.

Other Variables Influencing Outdoor Usage

Several other factors were found to be significant and were controlled for in the analysis. Age was negatively correlated with outdoor usage, and people using walkers or wheelchairs spent less time outdoors. Women and men had roughly equal outdoor usage, but people with pets spent considerably more time outdoors. People who reported they "cared very much about being outdoors," "felt more free outdoors than indoors," and/or "preferred to walk outdoors rather than indoors," also spent more time outdoors. Surprisingly, people spending more time outdoors were also more worried about falling outdoors; this might be due to having more opportunities to notice existing hazards and barriers in the environment.

Future Studies

Further research could build upon this study, using structured interviews, behavior mapping, and design interventions that measured the difference in outdoor usage between an existing environment in which one of the landscape features had been modified.

Application to Landscape Architecture Practice

In a society with diminishing resources and a rapidly aging population, it is increasingly important to find cost-effective ways to promote and maintain health in older adults. Landscapes that promote healthy behavior have the advantage of being relatively permanent and inexpensive after initial investment. Unlike programmed activities that require the ongoing cost and availability of staff to provide continued services, the environment can provide health-promoting opportunities on an ongoing basis, at the cost of basic upkeep and maintenance. These findings can help landscape architects design outdoor environments that support the actual needs of residents, and can also help convince decision makers to increase budgets for user-friendly landscape design and improvements. Although this study was conducted in assisted living, most of the concepts also apply to other levels of care such as nursing facilities, senior apartments and CCRCs (continuing care retirement communities). The core design concepts have been incorporated into a DVD-based educational program (20) which is now available to practitioners. The evaluation tool used in this study is being further developed for use by design practitioners and administrators, and will soon be available as well.

References

- Connell BR, Sanford JA, Lewis D. Therapeutic effects of an outdoor activity program on nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2007; 21(3/4):195-209.

- Fujita K, Fujiwara Y, Chaves P, Motohashi Y, Shinkai S. Frequency of going outdoors as a good predictor for incident disability of physical function as well as disability recovery in community-dwelling older adults in rural Japan. Journal of Epidemiology 2006; 16(6):261-270.

- Jacobs J, Cohen A, Hammerman-Rozenberg R, Azoulay D, Maaravi Y, Stessman J. Going outdoors daily predicts long-term functional and health benefits among ambulatory older people. Journal of Aging and Health 2008; 20(3):259-272.

- Takano T, Nakamura K, Watanabe M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2002; 56(12):913-918.

- Cutler LJ, Kane RA. As great as all outdoors: A study of outdoor spaces as a neglected resource for nursing home residents. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), The Role of the Outdoors in Residential Environments for Aging (pp29-48). New York: The Haworth Press; 2005.

- Cranz G, Young C. The role of design in inhibiting or promoting use of common open space: The case of Redwood Gardens, Berkeley, CA. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2005; 19(3/4):71-93.

- Rodiek S. A missing link: Can enhanced outdoor space improve seniors housing? Seniors Housing and Care Journal 2006; 14:3-19.

- Berentsen VD, Grefsrod E, Eek A. Gardens for People with Dementia: Design and Use. Tonsberg, Norway: Ageing and Health, Norwegian Centre for Research, Education, and Service Development; 2009. Available at www.nordemens.no/?pageID=138

- Cooper Marcus C. Alzheimer’s garden audit tool. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), Outdoor Environments for People with Dementia (pp179-191). New York: The Haworth Press; 2007.

- Grant CF, Wineman JD. The garden-use model – An environmental tool for increasing the use of outdoor space by residents with dementia in long-term care facilities. In S Rodiek & B Schwarz (eds), Outdoor Environments for People with Dementia (pp89-115). New York: The Haworth Press; 2007.

- Regnier V. Design for Assisted Living: Guidelines for Housing the Physically and Mentally Frail. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2002.

- Zeisel J. I’m Still Here: A Breakthrough Approach to Understanding Someone Living with Alzheimer’s. New York: Penguin; 2009.

- Lang R, Dhavale D. Beyond megalopolis: Exploring America’s new “megapolitan” geography. Metropolitan Institute Census Report 05:01; 2005. Accessed 5 February 2007 from www.mi.vt.edu

- Fovell R, Fovell M. Climate Zones of the Conterminous United States Defined Using Cluster Analysis. Journal of Climate 1993; 6:2103-2135.

- Carstens, D. Y. Outdoor spaces in housing for the elderly. In C. Cooper Marcus & C. Francis (eds.), People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space. New York, John Wiley & Sons; 1998.

- Carpman, J. R. Gaining access to nature. In J. R. Carpman & M. A. Grant (eds.), Design that Cares: Planning Health Facilities for Patients and Visitors. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass; 1993; 199-216.

- Cooper Marcus, C. & M. Barnes, Eds. Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations. New York, Wiley; 1999.

- McBride, D. Nursing home gardens. In C. Cooper Marcus & M. Barnes (eds.), Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations. New York, Wiley; 1999.

- Tyson, M. M. The Healing Landscape: Therapeutic Outdoor Environments. New York, McGraw-Hill; 1998.

- Rodiek S. Access to Nature for Older Adults. Three-part DVD series; www.accesstonature.org. Center for Health Systems & Design, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX; 2009.

Project Resources

Funding Support

The National Institute on Aging

Ronald L. Skaggs, HKS, Inc.

Texas A&M University

Susan Rodiek, Architecture

Chanam Lee, Landscape

Roger Ulrich, Landscape

Marcia Ory, Public Health

Mardelle Shepley, Architecture

Kirk Hamilton, Architecture

James Varni, MD, Landscape

May Boggess, Statistics

Matt Cefalu, Statistics

Eun Jung Kim, Landscape

Tony Forshage, Landscape

Jon Rodiek, Landscape

Chuck Huber, Public Health

Ross Larson, Public Health

Philomene Balihe, Public Health

Sang Nam Ahn, Public Health

Zhe Wang, Architecture

Adam Panter, Architecture

Susan Pedersen, Educ. Psychology

Judy Pruitt, Health Systems & Design

External Experts

Clare Cooper Marcus, UC Berkeley

Lois Cutler, University of Minnesota

Teresia Hazen, Legacy Health, Portland, OR

David Kamp, Dirtworks, New York, NY

Jack Carman, Design for Generations, LLC

Elizabeth Brawley, Design Concepts Unlimited

Patrick Smith, Pi Architects, Austin, TX

Margaret Calkins, IDEAS Institute, Kirtland, OH

Mark Epstein, ESA Adolfson, Seattle

Daniel Winterbottom, University of Washington

John Zeisel, Hearthstone Alzheimer Care

Jeffrey Anderzhon, Crepidoma Consulting

Diane Carstens, Gerontological Services, Inc.

Victor Regnier, Univ. of Southern California

Yvonne Westerberg, Haga Health Garden, Sweden

Jerry Weisman, University of Wisconsin

Uriel Cohen, University of WisconsinRachel Kaplan, University of Michigan

Naomi Sachs, Therapeutic Landscapes Network

Martha Tyson, Access Gardening, LLC

Erja Rappe, University of Helsinki

Paivi Topo, University of Helsinki

John Marsden, Mount Mercy College

Alee Karpf, Acer Institute, LLC

Nancy Chapman, Portland State University

Ben Schwarz, University of Missouri

Thomas Fairchild, University of North Texas

Patrick Grahn, Swedish Agricultural University

Johan Ottosson, Swedish Agricultural University

And

Norwegian Centre for Dementia Research:

Ellen-Elisabeth Grefsrod

Vigdis Drivdal Berentsen

Arnfinn Eek

Photos/ Graphics

Susan Rodiek

Igor Kraguljac

Zhipeng Lu

Elton Abbott

Mike Droske

Nandita Raghu

Anjali Venkataiah

Russell Reid

Manas Gopujkar

Taner Ozdil

Jin Rao